Then when I went home that summer, I watched with even greater anticipation for letters from Knox students I'd met the previous school year. The situation had become reversed: I was separated from new friends, and a place where I'd begun to feel more at home than my home in Pennsylvania.

The letters I got told of similar feelings--of frustrating jobs, boredom and loneliness. "I'm going crazy" was a frequent message. One admitted ruefully to a longing to get back to school, but that was implied in several more. The center of our lives had relocated.

The letters were also something like literary efforts: self-referential (offering a running commentary on themselves) and playful (puns especially.) My letters back certainly were that way--a reason to write, offer observations and opinions, construct fictions and jokes. One recipient got a call at work from her mother, alarmed that she had received a letter from the Howard Johnson Hotel Complaint Department. She went home at lunch time to find it was just a letter from me, stuffed in a purloined letterhead envelope.

In general, the letters allowed us to reveal interests and a personality that couldn't be expressed in the same way on home grounds. The bulk of my correspondence was with a young woman I won't name--even a half-century later, I feel the need to be discrete on her behalf. Our letters were exploratory but ardent and personal. We also exchanged poetry we'd written, and I sent her a short story I wrote that summer. When fall came our relationship faltered, but her letters were a lifeline that summer.

In response to my letter about events at the end of the school year, I got a letter or two from Mary Jacobson that I can't find. I recall she passed on a compliment on my writing from Jay Matson, editor of our literary magazine that evidently can No Longer Be Named. (I agree completely with the decision to dump all official uses of Siwash and Siwashers, but let's face it--the magazine was the Siwasher then, though it appears Knox College no longer describes it as such.)

I remember this compliment because it was one of the first indications I had that my literary writing might be worth pursuing. I also remember Mary writing that she had just read the Thomas Mann story, "Disorder and Early Sorrow." I loved the title all right, but found the characters and the story uncompelling, and didn't finish reading it. But I kept such judgments to myself, while I was learning.

Among the letters that did survive are several from Judy Dugan, a couple from Jim Miller (my Anderson House roommate), and a few from classmate Jill Crawford. Evidently I'd sent Jill a copy of J.D. Salinger's Nine Stories, and she wrote back enthusiastically about the book, describing the stories she liked best. She also read the two long Glass family stories collected in Raise High The Roof Beam, Carpenter and Seymour: An Introduction, as well as re-reading the two Glass stories in Franny and Zooey.

I'd read all of those as well, and in fact the only book I associate with that summer is Salinger: A critical and personal portrait, edited by Henry Anatole Grunwald. It's a collection of literary essays, book reviews and commentaries by such leading critics of the day as Arthur Mizener, Alfred Kazin and Leslie Fiedler, though the longer and more formal articles were generally by lesser-knowns. I remember reading it in the bright sunlight in my backyard.

Looking back, that book was probably important for me because it contained a number of differing critiques and evaluations, as well as literary analysis, of a writer whose small body of work I already knew. I had yet to take a college class that required this kind of literary analysis. I was still learning about it by osmosis. It certainly helped that I knew the work being discussed, so I could more or less concentrate on what kinds of things these writers said about it, and how they said it.

I probably was a little aware of this at the time, though it wasn't my principal motive. I was still deeply involved in Salinger's work, and I read this volume of criticism to enrich my experience of the writing. I found some of what I felt articulated, and also plenty to argue with.

Some of the essays and reviews compared Salinger to other authors, which gave me names of books and writers to explore. Fitzgerald was mentioned more than once, for instance, and The Catcher in the Rye compared with Huckleberry Finn. Salinger was very popular in the early to mid 60s, and so some of the critics bemoaned the attention he got over other contemporary writers they named who they considered more worthy. So, more names and more books to investigate.

References to Zen and eastern religions piqued my curiosity, just as Salinger's own mention of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus sent me to the Seton Hill College library in high school to peruse a volume of his writings.

|

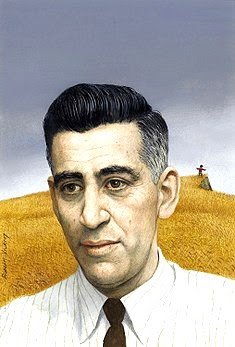

| portrait of Salinger on the cover of TIME 1961 |

The pieces I liked best articulated aspects I valued, but did so better than I could. One of these was by literary critic Ihab Hassan (who went on to have a distinguished career), another by a college-age student, Christopher Parker (writing mostly about The Catcher in the Rye.) They both emphasized the theme of a stubbornly retained openness and innocence--championing innocence as an important ethical element. Salinger's popularity tracks with the first baby boomers reaching adolescence. This theme is essential to understanding our experiences and responses, particularly in the second half of the 1960s.

One of the subjects of those letters from home to campus the previous spring had been about summer job prospects. There seemed to be several decent ones, but none happened.

Finally my father got me a job at the Hempfield Township Supervisors office. The township of Hempfield surrounded the city of Greensburg, though much of it was to the west. It was at least as old as the city, beginning with a few large farms in the 18th century. It was now where the postwar housing and population growth was going. My family lived at the nearest edge since the early 1950s, just a couple of city blocks or so outside the Greensburg city limits, in the district called Carbon, for the mine that used to be there.

Housing was expanding farther out even faster in the 60s, with lots of roadbuilding and so on. My father was at the time the de facto head of the township's "auxiliary police," which basically did crowd and traffic control as volunteers. He knew the main administrative supervisor, a fellow Democrat, who wanted to create an actual township police (paid, and with police powers.) The proposal was to be on the ballot in the fall. My father was set to become the Chief.

So he had some pull and I was hired as one of the young guys with very inspecific job duties. At first I was sent out with the other two guys to assist the ancient township surveyor, as boring a job as you can imagine, especially in the hot sun. One of our jobs was fashioning wooden stakes, at which I was spectacularly incompetent.

|

| Westmoreland County courthouse, where I did research and occasionally viewed trials |

Eventually he assigned me the job of researching and writing a report on why having a police force was a good idea. I did, the report was issued officially and written up in the newspaper--with my father named as the author. My first experience as a ghostwriter. However, the police measure failed in the fall, and all that remained of the township police force was a premature gold badge marooned for decades in a basement drawer.

The other aspect of working there I recall--apart from the ambiguous attentions of the township secretary, who chatted enthusiastically about her children as she stroked my arm--was the complaint by the Republican supervisor that I was reading on the job. Apparently, when I had no assigned duties, it was okay for me to sit and do nothing, but on no account could I read a book. It was a peek at the working world I would remember.

There were plenty of events on the television and in the newspapers that summer: a couple of Gemini missions and the first flyby of Mars, and after years and years of debate and some drama that summer, both the Voting Rights Act and Medicare passed Congress and were signed into law.

At the same time, there was strife surrounding civil rights demonstrations in Selma and elsewhere in the South, and in August the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles erupted in six days of violence that resulted in 34 deaths and nearly 300 businesses, public and private buildings burned and destroyed.

In June, the number of U.S. ground troops in Vietnam was increased to 72,000 from the initial 3500 sent in March. In July, that number was increased again, to 125,000, with draft calls doubled to 35,000 a month. Anti-war demonstrations continued in Berkeley and a teach-in was held in Washington.

I wrote several letters to the editor published in the Greensburg Tribune Review, often responding to the right wing rantings of an ultra-conservative retiree and frequent letter writer: I defended Medicare (then called "medical care for the aged") and Vietnam war Teach-Ins, and supported Senator Robert Kennedy's efforts to encourage nuclear proliferation treaties. Something to do in the vacuum of summer.

My big trip of the summer was to New York City in August. Knox student David Altman was something like assistant station manager at the campus radio station, WVKC, and I had just been named News Director. He was at NYU for the summer and invited me to visit, and stay in the dorm.

NYU is located in Greenwich Village, so I was keen to visit the folk music clubs there. I also saw my first off-Broadway plays: what turned out to be the original production of the Albee/Beckett double bill of Zoo Story and Krapp's Last Tape. After seeing Knox studio theatre productions of such contemporary plays, I was at first disconcerted to see adult characters being played by actual adult actors.

We spent a desultory day at the 1964 World's Fair, smothered by the heat and discouraged by the lines. Towards the end of my stay, I took a train up to Darien, Connecticut to visit classmate Sue Barry. I drank beer out of a pewter mug and saw my first four-way stop signs. I'd written to Sue earlier in the summer about my New York trip, and she invited me to visit. She mentioned that the Newport Folk Festival would be happening in late July, but I didn't get to New York until August. That festival would go down in history for Bob Dylan's first "electric" performance with amplified back-up, comprised of players who would later form the Band.

I also had some musical business to do in New York. I carried with me a tape of several original songs that my folk trio the Crosscurrents recorded in my basement earlier in the summer. I'd written most of them. I looked up a talent agency and took it to the address. They told me to wait and someone would see me.

In the waiting room a slightly older guy advised me that if I had doubts about the quality of my material I should leave, because you usually got only one chance. But I couldn't come back, so I stayed. A middle aged man came out and started walking me back to where he would play my tape, his arm on my shoulder. He was asking about me in a friendly way, and as he held my tape casually inquired what the speed was. These were reel-to-reel days.

I said 3 and 3/4. He stopped. He was sorry but they didn't have the equipment to play back at that speed. Most home recorders had options for 3 3/4 and 7 1/2. The slower speed meant you could get more on the tape, though at lower quality. But professional recording was done at 15, and their machinery could play back only that and 7 1/2. So I left the building without our songs being heard.

As it turned out, that would be as close as the Crosscurrents got to folkie fame. I found myself blinking in the sunshine, having had my hopes raised and dashed in a matter of moments.

There was a movie theatre across the street, which promised darkness and air conditioning cold. I went in. And it was that moment that changed my life. It was the afternoon and only a few people were in the theater, but I was sure that one guy I saw in front of me was Bob Dylan. I got a pretty good look at him walking past me--he left in the middle of the film.

The movie that was playing was Help! by the Beatles. It was new that summer. I walked into the theater a folk music snob, and walked out a Beatles zealot. The music, the style of humor, everything about it blew me away.

I'd been into rock and roll in the 50s (Buddy Holly was my guy) but left it for jazz in high school and then folk music. I saw the Beatles on Ed Sullivan and all the screaming girls, but it was radio pop, not serious or meaningful or relevant like folk music, so I had no reason to see the Beatles' first movie, A Hard Day's Night.

That all started disappearing in the wake of Help!'s opening credits. By the first musical sequence, the recording of "You're Gonna Lose That Girl," it was gone. By the ski scenes to "Ticket to Ride" I was transformed.

When I got back home I assembled the Crosscurrents, and we went to see the movie together--several times. (Another time soon after that we saw it again on a double bill with A Hard Day's Night--both of them several times. Back in Galesburg in the fall I repeated the process at the Orpheum theatre. I started in the afternoon and was still there for the last show in the evening, when I saw Doug Wilson walk in.)

Back at his house after the movie that summer, Clayton figured out the chords to all the movie's songs while his younger sister Taffy wrote out the words from memory. We (Clayton, Mike and I) played them over and over in a frenzy in Clayton's basement, much to the delight of his many younger siblings. So many things changed, so much of our future direction was reset--musically, culturally and even for me, in my reading and literary pursuits. It was a new ticket to ride.

No comments:

Post a Comment