|

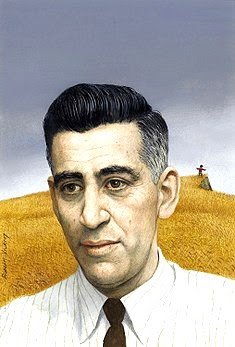

| William V. Spanos, 1966 Yearbook photo |

He was easy to spot, and easy to parody. Mike Hamrin in a fake black beard did a good job for one of the Mortarboard satirical skits, in a scene set at the Gizmo picnic table where faculty met, next to his friend Doug Wilson (played in this case by himself.)

His unique characteristics were on full display in his classroom, along with his repertoire of mannerisms. The one I remember best was a twisting of his hand, fingers slightly splayed, as he worked his way to a complex point: he appeared to be changing a phantom light bulb, or screwing the lid off an invisible jar hovering upside down above his shoulder.

Though he perpetually seemed to be slightly angry about everything, and his glowering intensity and insistence on taking everything so seriously could be intimidating, he could also be kind, compassionate and companionable. He may not have had much of a sense of humor about anything else, but fortunately he did have one about himself. I got to know him and his wife a little that year, went on a road trip to Wisconsin with him, socialized a bit and served as babysitter a few times in their home. But even now, when it feels appropriate to be referring to Sam Moon and Doug Wilson, I can't bring myself to call him Bill. He's forever Mr. Spanos.

I recall this Types of Poetry course as a large one, with juniors and seniors among the second years. Mr. Spanos defined his mission at the first class: Most people don't know how to read a poem. They get a feeling, as he said with undisguised sarcasm. But true poetry is not sentimental mush. Poems make statements--they assert, narrate, ask questions, provide if/then arguments and internal debates.

There are sentences in the lines of poems, with subjects and verbs and objects, however they are ordered. The pronouns refer to something: the 'it' in the 7th line of the third stanza in Yeats' "Sailing to Byzantium" refers to "heart" in the fifth line, for instance. Poets use devices, sound patterns, rhyme schemes, themes, ambiguity, irony, paradox ("To that sweet yoke where lasting freedom be," Sir Philip Sidney in "Leave me, O Love.") In the course, we were going to learn how to read what's really there in some of the best poems in the English language.

Our main text was 100 Poems: Chaucer to Dylan Thomas, edited by A. J. M. Smith (Scribner's 1965.) Along with the poems, the Glossary of Technical Terms in the back proved useful. These poems were supplemented by others in handouts. Mr. Spanos impressed upon us that there was a lot in each poem to discover.

He did that partly by spending what seemed like weeks on the first poem in the collection, that in its entirety is four lines, by an anonymous poet: Western wind, when wilt thou blow./The small rain down can rain?/ Christ, if my love were in my arms,/And I in my bed again!

We spent another year on the first two lines of Chaucer's Prologue to the Canterbury Tales in Middle English. Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote/The droghte of March hath perced to the roote... But once you know "shoures soote" means "showers sweet," then let the metaphor begin.

I have my copy of 100 Poems from this class, with my circles and arrows to my marginal notes on Spanos' analysis. He points out a troche (two syllables, first stressed) and the places where Shakespeare shifts his rhetoric from negative to positive and back to negative again in his Sonnet CVI, which pits Platonic ideals against the changeableness of human nature: "Let me not to the marriage of true minds/ Admit impediments." The line continues "Love is not love/Which alters when it alteration finds," which means one thing when "alters" and "alteration" refer to the same sort of behavior, but something else with the Elizabethan meaning of "alteration" as the ravages of time.

(There's another note I made that probably went right by me at the time, but now that I've become more familiar with Shakespeare's plays, it's brilliant: "Mixed metaphors (to be effective) must be analogous images." Shakespeare deploys cascades of mixed metaphors--see Hamlet's "To be or not to be" speech alone--but because the images are analogous, they work together.)

We spent a lot of time on Thomas Wyatt's "They Flee From Me"--the rhyme scheme, the movement from present to past and back, the ironies, the reversal of the traditional metaphor of man the hunter and woman the hunted, but also the poem as a reflection of the historical moment: it was a lament on the rise of the "newfangledness" of courtly love. Yet knowing this did not disturb, and does not disturb, the phrases and elements of language that attracted me, and that continue to work their magic on the level of (don't tell anybody!) feeling.

And so it went, with large cultural themes and hidden antinomies, disparaties, dichotomies, ambiguities...existential implications, sexual metaphors, symbols and allegory, persona and allusions, verse forms and rhyme schemes...By the time we got just to Dryden (1631-1700) the class was thoroughly intimidated, which led to my one moment of glory (sort of) that I remember.

We were looking at "A Song for St. Cecilia's Day," and Mr. Spanos began by asking the class, "What kind of poem is this?" Silence, for an uncomfortably long time. I timidly put up my hand. "Occasional?" I offered. "It's an occasional poem!" he thundered in exasperation.

It wasn't exactly a genius flash of insight on my part. The title says it--it is a poem marking the occasion of St. Cecilia's Day. It even includes the date. But after all these areas of arcane mysteries had been revealed, the obvious looked like some sort of trick.

In old pages of my persistent college fictionalizing, I came across a scene that might come from this class. If it didn't happen that way (as my Aunt Toni used to say) it could have. It centers on a poem that's not actually in the 100 Poems collection, a very short lyric by Robert Frost called "Dust of Snow":

The way a crow

Shook down on me

The dust of snow

From a hemlock tree

Has given my heart

A change of mood

And saved some part

Of a day I had rued.

In my pages, "Mr. Spiros" insists the poem is scatological: "'This person--the persona of the poem, some young kid with a broken heart--' Spiros deeply sang the words in the measure of ridicule--'who goes out, burdened with sadness and suicide, like students like to go out in the rain, feeling abysmally sorry for themselves, and loving it. This persona is standing under a tree, and up in the tree a bird shakes some snow on him. For a moment he thinks its bird droppings that have fallen on him. But then he realizes it's snow and he laughs in relief. He laughs at himself.'"

In my fiction, the "persona" is a student who scribbles down his own version of what a Spiros version of Frost's poem might be:

The dust of snow from a hemlock tree

fell down and revolted me.

'If you don't have the courage

or the good sense,

shit on somebody else

who isn't so tense.'

Nervous was I

when I spoke out these words

to take the snow from a tree

for spineless bird turds.

But I grew wise

as I grew old

and realized turds

are not that cold.

It does sound like something Spanos would say, and the kind of doggerel I wrote during classes. We were assigned to read more poems than got marginal notes in my text, but I'm not entirely sure which ones. There's nothing marked in Blake, though we must have done at least "The Tyger." We must have blitzed through Wordsworth (pausing to note the rhyme scheme of his sonnets) and the rest of the English Romantics, the 19th century Americans. (The editor's judgment was also part of it--one Byron, lots of Keats, one Emily Dickinson.)

The notes pick up when we reach Yeats, and explode with Eliot's "Gerontion" and "The Hollow Men." And that's more or less where we would return in the Spanos spring course, Modern British and American Poets.

Before that however, a little about the supplementary text for this Types of Poetry course: A Prosody Handbook by poets Karl Shapiro and Robert Beum (Harper & Row 1965.) Notice that both this and 100 Poems were new that year. Of the two, only A Prosody Handbook remains in print, which is odd only in the sense that the authors' foreword made it sound like only the latest in a long line of books on prosody, and apt to be replaced at any time as ongoing debates are resolved. But it's still around.

According to the two poets: "A poem yields up its meaning, and makes that meaning an experience, in two ways: (1) through the semantic content of words that are organized in sequences of images, ideas, and logical or conventional connections; and (2) through the "music," the purely physical qualities of the medium itself, such as sound color, pitch, stress, line length, tempo."

Prosody has to do with the music, the sound. "In recent decades, the study of poetry has focused intensively on the semantic elements of the poem, and prosody has been somewhat neglected," the authors assert.

Spanos probably leaned that way, too, but he dutifully included prosody in his discussions of individual poems. Shapiro and Beum write that teachers should feel free to assign their book without going through it point by point, and to my recollection that's what Spanos did.

Fortunately, this book also has a useful glossary, which is probably how I used it. That's not because I disdained prosody (though even now I find the early going in this book confusing.) If anything, all the new knowledge about semantics seemed to devalue my natural attraction to the sound.

That's been true in my own writing, prose and verse: the music is its greatest strength, and therefor at times its greatest weakness. But I no longer am intimidated about this preference. Robert Frost is known for his country wisdom, Wallace Stevens as the premier poet of ideas, and Edward Albee for the riveting characters in his plays. But all three said that sound is primary in their work. It's the rhythm, the sound of words, the music.

Reading poems in this analytical way inevitably involved interpretation, and the ongoing question was what made an interpretation valid? Those attracted to poetry could become defensive if their experience of the poem was demeaned. Were they "mis-reading" the poem, or simply getting something else out of it?

Such conflicts could get quite emotional. Interpretation quickly gets into the realm of literary criticism, and methods or styles of criticism can change. The dominant style at Knox in 1965 seemed still to be the New Criticism of the 1940s and 50s. Even as early as this Types of Poetry course, there were at least a couple of works of criticism referenced. In any case, I'm pretty sure I bought my copy of The Well Wrought Urn by Cleanth Brooks that spring (copyright 1947.)

While Mr. Spanos may have shortchanged the evocative somewhat, this Types of Poetry course imparted skills in reading and analyzing that revealed and enriched the experience of the poems. On that essential level, it was one of the more important courses I took. Spanos balanced his own critical point of view and enthusiams with the nuts and bolts analysis--scanning the lines, noting the spondees, revealing the meaning--and double-meanings-- of words at the time they were written, and so on. However, in the spring course he gave freer reign to his own insights and point of view. He took us on journeys deeper into the poems.

For this British and American Poetry course The Imagist Poem, an anthology edited by William Pratt. was the first paperback we used, mainly to trace the historical path to modern 20th century poetry that proposed centering on the accurate and original image, using ordinary words, in a rhythm that corresponds to the emotion evoked by the poem. The model was Ezra Pound's: The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough.

Most of the course as I remember it concentrated on William Butler Yeats, T.S. Eliot and Pound. (I seem to recall that Spanos wanted to add a more contemporary poet, like Stanley Kunitz, but we didn't get that far.)

In Yeats' Selected Poems and Two Plays (edited by M.L. Rosenthal) we certainly read "The Second Coming" though I have more marginal notes on the lesser known poem that follows it--"A Prayer For My Daughter." We read "Among School Children" and the Crazy Jane poems. Classmate Leonard Borden reminds me of one short poem that got the full Spanos treatment--which he points out is particularly apropos for us these days:

Speech after long silence; it is right,

All other lovers being estranged or dead,

Unfriendly lamplight hid under its shade,

The curtains drawn against unfriendly night,

That we descant and yet again descant

Upon the supreme theme of Art and Song:

Bodily decrepitude is wisdom; young

We love each other and were ignorant.

So emphasized and drummed into our heads was this poem that I parodied a few lines of it in my short story published later this spring, "The Pressure of Reality."

We read a lot of Pound, no poem more intensively than the very long "Hugh Selwyn Mauberly." My notes are extensive, and include analysis by John Jacob Espey, evidently from his book on this poem. It's not surprising then that Spanos published a long article on Mauberly in Contemporary Literature, where he dealt with the issue of who is speaking--the persona. I have an undated reprint so I don't know whether it was a class handout or came later.

"Mauberly" in particular was an apt transition to T.S. Eliot. While we used the New Directions paperback of Pound's Selected Poems, we got the hardback edition of Eliot's The Complete Poems and Plays 1909-1950. I believe it came without a dust jacket--just that firm, deep green book that was like modernist scripture.

We did the major poems (though not the ones that would ultimately be the most famous--the Book of Practical Cats poems that were the basis of the international hit musical Cats): "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," "The Wasteland," "Gerontin" and at least one of the Four Quartets, plus some of the lesser known poems, and perhaps a play, and certainly the essay "Tradition and the Individual Talent" (not included in this volume.)

This book is less marked up--maybe because I was reluctant to deface a hardback I was likely to have for awhile. Some--perhaps many--of my classmates had been acquainted with at least Prufrock in high school, as Spanos himself had been when Eliot was alive and fashionable. But with the possible exception of "The Hollow Men," Eliot was all new to me. Such was the power of these Eliot poems that they seemed to permeate that entire spring--but more about that in a future post.

Eliot got into our heads--he seemed suddenly to have invaded the whole campus--but I was also intrigued by Pound. I bought his ABCs of Reading that spring, and other books of his poems and prose for several years after. According to a notebook I ineptly kept that school year, I also read at least some of Hugh Kenner's The Poetry of Ezra Pound. I would later acquire and read his opus on this generation of writers, The Pound Era (1971.)

This British and American Poetry course (in which none of the poets were, strictly speaking, completely British or entirely American) was one of the last Spanos taught at Knox. He left at the end of the spring semester, taking a position at what would become the State University of New York at Binghamton, where he taught for the rest of his academic career.

Spanos was part of the second wave of the faculty exodus in my Knox years. Others who left then included Kim Chase, my sociology professor Michael LaSorte and respected history teacher Gordon Dodds. I took 18 courses in my first two years. Eight of them were taught by faculty members who weren't around for my third year.

Students continued to express concern if not outrage about this exodus, which this year numbered at least 17. More than twenty Sociology students and fifty Economics students signed letters of protest in the Knox Student. Bill Barnhardt wrote an editorial on it, commenting "It is one thing to experience 'mobility' among the faculty, a growing trend in higher education, and quite another thing to witness the one-way drain of academic talent from the campus."

In a draft of his autobiography that he circulated privately, Spanos attributed his leaving Knox to a desire to devote more time to scholarship, which student demands on his time precluded. His essay in the Spring 1966 issue of Dialogue tells a different tale--of disillusionment with the college, and despair that it will change for the better, especially in view of this exodus of young faculty.

Also that spring, he signed for me a reprint of an article he'd published (which unfortunately I can't find.) I recall it said something like "with pleasant memories of a interesting year, despite"--and here I am sure of his words--"the persistent bad faith." In a Sartrean sense, bad faith may simply mean conformity, but perhaps in this context something more.

1965-66 was also the year that Dennis Parks brought ceramics-making to Knox, which attracted a lot of people I knew to "throwing" pots in the new studio--something that changed the lives of students Tom Collins and Harvey Sadow, who became famous ceramicists. Doug Wilson got into the process as well, and probably as a going away gift he made Mr. Spanos a huge serving plate, upon which the words "Man, God, Art" ran vertically, intersecting like a crossword with the appropriate letters in the word that ran horizontally: Spanos.

My notebook records a party that winter that student James Campbell gave for Spanos on the publication of his first book, which at that time no one had yet seen, including him. But eventually his Casebook on Existentialism made it into the Knox Bookstore, which in those days actually sold books. This book became arguably his most influential, in this and a later, expanded edition.

Over the next decades Spanos published some 15 books, not including those he edited. In 2015 Northwestern University Press published a selection of essays titled A William V. Spanos Reader:Humanist Criticism and the Secular Imperative. He is referred to as a "pioneer of theory," meaning the postmodern theory that dominated universities especially in the 1980s and 90s. He also founded one of the most influential journals of postmodern analysis, Boundary 2.

Unfortunately for me, the little I sampled of his work in this era I found unreadable, as I did most of this kind of criticism. The specialized language (or jargon, depending on your point of view) was so dense as to render the old idea of a sentence--or a verb--inconsequential. But his intentions are fairly clear. Spanos expanded the New Criticism kind of reading to include political and cultural implications. He championed 'the full obligation to think the question of the human in an absolute sense: every single minute of one’s waking life.' And in a 2010 book, his most personal, we learn why.

In 1945, waves of British and American warplanes firebombed the undefended city of Dresden, Germany, and reduced one of the most beautiful cities of Europe to ashes and agony. In sheer destruction it rivals Hiroshima, but it was not widely known, during or after the war, until 1968, when Kurt Vonnegut's celebrated novel Slaughterhouse-Five dramatized it. (I knew of it years before however, because I read about it in a combat comic book, which celebrated it. The drawing of incendiary bombs lying on rooftops to be ignited by the sun stayed with me.)

As a young US soldier and prisoner of war, Bill Spanos was present during the bombing of Dresden and its aftermath. He wrote about it in that 2010 book, In the Neighborhood of Zero.

I did not know this about Mr. Spanos, and I doubt if many at Knox did. It seems he did not talk about it--at least in public-- until after Slaughterhouse Five brought the Dresden bombing into public discussion, including the charge that it qualified as a war crime.

That would have been at least two years after he left Knox. It may have been longer. That was not uncommon among World War II veterans. But I marvel now at the mental picture of Spanos, witness to Dresden, sitting at that Gizmo faculty picnic table next to history professor Miki Hane, who had once attended school in Hiroshima.

I had no trouble reading In the Neighborhood of Zero--it is a remarkable, powerful book. It is a memoir of his experiences as a young Greek American in the Army, the chaos of combat in the Battle of the Bulge, his capture by the Germans, the days of transport in a sealed boxcar with so many other men that they had barely enough room to stand, and his months of labor and privation as a prisoner in Dresden. All of this before the sustained terror of the bombing, and the shock of the aftermath, when he and other POWs moved broken masonry to find rotting bodies, though some were even more horrifyingly well preserved.

His narrative continues through a forced march with other POWs ahead of the Allies invasion, his escape, and after a strange interlude with two German civilian women, his re-connection with the US Army, and his dehumanizing voyage home.

If this were a book and the story of a perfect stranger, I would find it gripping and illuminating. Some awkward writing only adds to the sense of an earnest struggle to tell his story as truly as he can. But it also sets off odd flashes of recollection concerning the Spanos I knew.

In his captivity he struggles to recollect a war poem he read in high school--it is Wilfred Owens' "Dulce et decorum est," which he would teach us in one of these classes, not from a book but a mimeographed sheet. It concerns a young soldier whose ideals are shattered by the realities in the trenches of World War I.

In his Knox class, Spanos was especially passionate about this poem, and the expansion of the Vietnam War then underway was an undeniable backdrop. When sifting through the rubble after the Dresden bombing he thinks of "a heap of broken images" from Eliot. But another Eliot line he quotes brings back a memory from outside of class.

Between the British and American bombing runs he remembers "...it was Ash Wednesday, around 10:30 in the morning--we returned to the sawmill where we were told to await further orders. I was physically and emotionally exhausted. My mind was like the sky in T.S. Eliot's poem, a 'patient etherized upon a table.'" It is one of Eliot's most famous lines, but it evokes for me an image of Spanos at a kind of spontaneous after-party late at night at his house in Galesburg, in which he, his wife and some other faculty and spouses were playing charades. When it was his turn he suddenly swept everything off a coffee table and lay down on it in the corpse position. It didn't take long for someone to guess the answer.

Spanos relates some personal reasons for not talking about or writing about these experiences for so long. He briefly mentions Vonnegut's novel, but his description of it is curiously reductive. He refers to the experience of Billy Pilgrim becoming "unstuck in time" as a mental breakdown, and his encounter with the alien Tralfamadorians as hallucination. This tends to devalue what the aliens (or Vonnegut) say about time--that events exist simultaneously like peaks on a mountain range. The past, present and future always are.

This is interesting because in this book Spanos also makes a powerful point about time. He begins the book by quoting an exchange with a student after a lecture on Vonnegut's Slaugherhouse-Five: "Did you ever return to Dresden, Professor Spanos?" "I never left there."

He ends the book after his return home, as he and his sister Kitty watch a parade on the day the war with Japan--and all of World War II--finally ended. His sister notices that he's quiet while everyone else is cheering. Why isn't he celebrating?

I don't know what to say to her in response... I'm physically here in Newport, which has become the center of the world, but in my mind and heart I'm far away, in the midst of another center. I'm in a sepulchral city of ashes, Dresden/Hiroshima/Nagasaki. The world of zero. And yet in a perverse way that I can't explain even to myself, I feel in the very abyss of my anguished heart, inextricably, the tentative stirring of a beginning not of a new story but a now time that bears within it, always, like a chalice, that infernal time. I say in response, "I am celebrating, Kitty. I am!"

Spanos is in a sense making a point about time similar to Vonnegut: that the past inhabits the present. But his emphasis is opposite to the Tralfamadorians, who say that they find the pleasant places in time and concentrate on those. Spanos commits to recalling the worst places, to inform the tasks and the meaning of the present.

And so emerges another dimension of a man I thought I knew. It shifts the focus of the memories, including the moments in class when he passionately insisted on finding the power and meaning in the books and the poems we read.