Earth Day #40: Classics

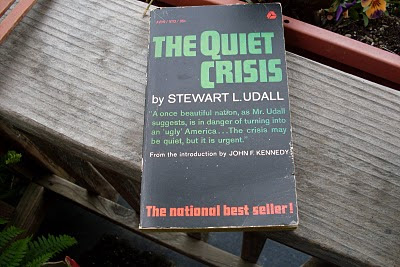

Stewart Udall, Secretary of Interior in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, died last month. A pioneer in environmentalism before and after the first Earth Day (and a major voice in the excellent PBS American Experience docu, Earth Days), he was the author of a mostly forgotten but very important book, The Quiet Crisis (1963). Following only a year after Rachel Carson's expose of chemical pollution, Silent Spring, Udall's book took a more historical view--chronicling American conservation efforts--and a wider view of the present: "In a great surge toward 'progress,' our congestion increasingly has befouled water and air and growth has created new problems on every hand. Schools, housing, and roads are inadequate and ill-planned; noise and confusion have mounted with the rising tempo of technology; and as our cities have sprawled outward, new forms of abundance and new forms of blight have oftentimes marched hand in hand."

Some books of bygone decades describe problems which the subsequent environmental movement addressed in America, while others--like Paul Ehrlich's The Population Bomb--dealt in terms now obsolete with problems that are still with us, and have even grown worse. But there are other books, like Udall's, that are of more than historical interest: they are classics both in the sense of being among the first to break new ground, and of enduring value to us now, including as reading experiences. They are classics, not only or not specifically of "environmentalism," but of all that pertains crucially to Earth, and Earth Day.

Udall's book was one of the first public policy books to recognize the importance of Aldo Leopold and his essay on "the land ethic," in the now classic book, A Sand County Almanac. Another writer of that era was Loren Eiseley, and to pick out probably his best known title--The Immense Journey--is to give only one example of his enduring writing, in a number of books.

The next generation of indispensible writers begins with Gary Snyder, in his poems but also in his prose statements, especially the landmark The Practice of the Wild (1990) but also The Old Ways (1977), The Real Work (1980) and A Place in Space (1995.) These helped to inspire the bioregionalism and rehabitation movements that were and are especially influential in the western U.S.

One of the most important figures in establishing the breadth and depth of the ecology movement--and one of the most forgotten, was Paul Shepard. His essay, "Ecology and Man, A Viewpoint" was a foundation document. Many of the ideas now entering the mainstream through newer authors were even more fully and gracefully articulated in his books, considered radical in their time, particularly the crucial importance of nature to childhood and human development (Nature and Madness) and the idea that "animals made us human" (even the phrase is originally his) in Thinking Animals, The Tender Carnivore and the Sacred Game, The Others and other books.

Today we pursue a deeper understanding of the Earth through the ideas that coalesce around the powerful image of Gaia. Various elements of that understanding come out of books that are still classics, such as the best-selling essays of Lewis Thomas in Lives of A Cell, and Gregory Bateson's Steps Towards An Ecology of Mind. Learning more about the ways in which our human ancestors related to the natural world (another major subject for Paul Shepard), is informed by a deeper understanding of surviving Indigenous peoples. A classic in this regard is Make Prayers to the Raven by Richard Nelson, who used this experience with the Koyukon elders to inform his own intense experiences in The Island Within.

We all have our favorite authors and their books describing their experiences in the natural world, but among the essential authors who combines description of experiences with a greater context, Gary Snyder is one of my favorites, and I revere especially his book, The Practice of the Wild.

Another book that was particularly important to me but which I feel is a classic that fills in an important conceptual area is the relatively unknown Ceremonial Time by John Hanson Mitchell. It is the history of a single square mile of New England, over 15 thousand years. It gives the dimension of time to place, and vice versa.

Finally, there are much more recent books on the most important topics concerning the Earth and its future, particularly in two areas. First is biodiversity and our understanding of both the deep interrelationship of life and the understanding of other species, particularly as we overcome the bias of the mechanistic interpretation of Darwinian evolution. I don't know if there are any classics in these areas yet, though landmark books would likely include Acquiring Genomes by Lynn Margulis and Dorion Sagan, and Evolution in Four Dimensions by Eva Jablonka and Marion J. Lamb. Books like Beast and Man by philosopher Mary Midgely and books by Elaine Morgan like The Acquatic Ape and The Descent of Woman are exciting to read and shake things up.

The other topic is the climate crisis, and in this area I have more definite choices: An Inconvenient Truth by Al Gore remains the classic survey of the subject, Forecast by Stephan Faris is the best account of the present consequences, while Down to the Wire by David Orr is the best book so far on the climate crisis future.

And now that I've been so definite, I have to take it back--these are my choices, books I would recommend as classics, but I haven't read everything so I'm sure I'm missing plenty.

No comments:

Post a Comment