Since I first wrote about the original Hardy Boys mysteries six years ago (in the History of My Reading series), there’s been some news.

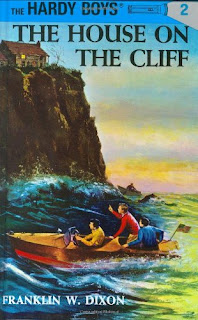

The Hardy Boys books began in 1927 with three titles, then three more in 1928 before the series settled down to issuing one title a year. Last year (2023) the copyrights on these original versions of the first three novels expired. That means they are in the public domain, and anyone can publish them, no permissions (or author payments) required. It also means that anyone can alter them or just publish them badly, with mistakes, changes and eliminations. But they are well published online at Project Gutenberg. They are: The Tower Treasure, The House on the Cliff and The Secret of the Old Mill.

The three titles published the next year, in 1928, presumably entered or will enter the public domain some time in 2024. They are: The Missing Chums, Hunting for Hidden Gold and The Shore Road Mystery. They are likely to appear online at some point this year. [UPDATE 3/35: These three are also posted now at Project Gutenberg.] [FURTHER UPDATE 2025: these and two more public domain titles are also available in paperback from Dover Publications.]

These are the original Hardy Boys novels, as written by Leslie McFarlane and edited by Edward Stratemeyer. McFarlane wrote 1 through 16, and 22 through 24, while other authors wrote the rest of the original 58, all under the name of Franklin W. Dixon.

|

| the revisions series |

Unfortunately the distinction between the originals and revisions is seldom made. For example, the online site The Creative Archive purports to publish the first 58 Hardy Boys novels online, but these are the 1950s-60s revisions, not the originals.

At the end of this post, I make some comparisons of the originals with the more widely available revisions. Four of these appeared in my post six years ago (in slightly different form), but I’ve added comparisons of two more: #3 The Secret of the Old Mill and #8 The Mystery of Cabin Island, which the unofficial Hardy Boys page calls “probably the most popular story among fans.”

On balance, I continue to greatly prefer the McFarlane originals. I recently chanced upon an article written by Gene Weingarten in 1998 entitled “The Ghost of the Hardy Boys” (included in his collection, The Fiddler in the Subway) that helped clarify my thinking.

Weingarten, a magazine feature writer and purported humorist, trashes McFarlane’s writing in these books before praising him as a literary artist trapped by financial circumstances into painfully turning out trash, namely the Hardy Boys books. (McFarlane seems to base his quality of writing judgments on the first book he picks up--The Missing Chums, which unfortunately isn't one of the better written.) This has become a familiar point of view on McFarlane, perhaps the prevalent one. I think it’s at best overly simplistic and on balance, deceptive and wrong.

|

| a young McFarlane |

But are the resulting novels possibly “the worst books ever written,” as Weingarten insists? Not hardly. For one thing, Weingarten hadn’t read the later revisions, which are arguably worse. But even in themselves, the McFarlane versions do not fully merit his critique, especially in style. He says it is “overwrought.” Apart from questions of taste (and Weingarten is very certain his taste is correct), there is the fact that these books were written for young readers, roughly ages 9 (the age when I started reading them) to 12. Weingarten provides an example of this overwrought writing: “Frank was electrified with astonishment.” It’s not a phrase appropriate for adult literary fiction perhaps, but it’s vivid language for young readers—many of whom are quite capable of becoming electrified with astonishment.

(It’s certainly more creative language that Weingarten uses to introduce this article: “I started working on it with a chip on my shoulder. I ended it with a lump in my throat.” Now that’s bad writing--"overwrought" doesn't cover it.)

Weingarten mocks the conversations conducted while the boys are riding their motorcycles, as if anyone could converse over that noise. While stretching credulity a bit, these are 1920s motorcycles ridden by teenage boys after all, and not the behemoths of today. In The Tower Treasure, a specific contrast is drawn between the “putt-putt” of their motorcycles, and the roar of an automobile. Certainly there is awkwardness and repetition in the writing, but that more or less goes with the genre, and can be part of its charm.

The Mystery of Cabin Island opens with a page describing the winter landscape in clear physical language and measured sentences that remind me of Hemingway. Nor was I surprised by Weingarten’s revelation that McFarlane was a devotee of Dickens—I got that from his books—especially the characters and set pieces that tended to be edited out of the revisions.

It is this language, as well as the period details, that charm many readers today. Although Weingarten quotes McFarlane’s granddaughter saying he hated these books (and his children are quoted elsewhere saying similar things), McFarlane is also directly quoted referring to his Hardys with some pride, saying that instead of the slapdash style of other boys books, “I opted for quality.”

By and large, the revisions I've read did not. In addition to changing plots and characters, with some bewildering story choices and careless writing, there were changes particular to reflect the J. Edgar Hoover 1950s obsessions with subversion, expressed in altered plots and an end to the skepticism of authority figures in the originals, especially local police. Says the Hardy BoysUnofficial Homepage: “The quality of the revised stories is generally so far below that of the originals that it can only be considered an act of literary vandalism.”

There's no question that some of the writing and vocabulary as well as the action in the originals reflect an earlier time. But that was true when I first read them as a boy in the mid-1950s, and I was charmed anyway. The fact that there weren't roadsters and touring cars anymore, or chums, even added to the appeal: the charm of the exotic. Reading them as an adult, I see them not as exotic but true to their time, in the modesty of the stories, their pace and organic quality, as well as evidences of a bygone era. And so I remain charmed.

Here are my comparisons:

The Tower Treasure (#1)

Another item in the brief was to shorten the books to the same length of 180 pages. So what took two chapters and 17 pages in the original is reduced to one chapter and 8 pages in the revised.

Some arcane language in the original is a bit disruptive, though funny, cf. "I'm going to ask these chaps if they saw him pass." But the revision goes further than updating words and eliding the story--it unaccountably adds incidents and characters, to no better effect than the originals. Plus it doesn't actually eliminate all ethnic stereotypes--just the ones people were more sensitive to in 1959.

It isn't long before the losses become obvious. The original has a comic set piece involving a group of farmers; the human comedy is entirely lost in the revision, as is the pretty realistic dialogue in the scene. Similarly a scene involving the small town police chief and his detective is derisively funny. That such scenes reminded me of Dickens is reinforced a few pages later by a reference to a character habitually carrying Dickens' novels (naming three.) The original also throws in a sly Shakespeare reference, a phrase from Hamlet.

But the loss of a certain literary quality is more telling in a line Fenton Hardy says to his sons on page 76 of the original, when he tells them they can help "by keeping your eyes and ears open, and by using your wits. That's all there is to detective work."

Later when the boys solve the mystery that has puzzled everyone (including their father), they conclude that "The main thing is that we've proved to dad that we know how to keep our eyes and ears open." (209) The symmetry of these lines more than anything else starts off this series of books. They are entirely absent from the revision.

The revision has the good sense to keep the subplot of the father of one of the Hardy Boys' school friends who is unjustly accused of a crime (a similar situation will be repeated in a subsequent book), even keeping most of the dialogue. But for every arcane line the revision eliminates ("Brace up, old chap") it seems to lose one of delicate feeling or meaning: "Frank and Joe, their hearts too full for utterance, withdrew softly from the room." (68)

This being the first novel, it has the first instances of official police incompetence, and Fenton Hardy's disdain for the local police. In the revision this is gone, though the comic futility of the chief and his detective Snuff is replaced by a comic and less convincing Snuff, now an aspiring private detective lost in self-importance, ambition and incompetence.

The climactic scene in the revision suddenly adds a character to increase threat and action (the 1950s Disney teleplay has its own version of this character though he appears early, and interestingly represents a seemingly friendly but ultimately untrustworthy and violent adult) but it adds little to the scene. The ending of the original is longer and more satisfying.

The original story begins with the Hardy Boys and their pals (or "chums") escaping summer heat with a motorcycle ride,which leads them to a remote abandoned house, reputed to be haunted. They do hear eerie sounds inside (which later turn out to have been staged to scare them away.) As they are leaving, Frank and Joe Hardy discover tools were stolen from their motorcycles. They later witness an attempted murder on a boat and rescue the victim, but he soon disappears. This begins another strand of the mystery.

The revised version begins with Fenton Hardy letting the boys in on a case in progress. This is another odd trend in the revisions: the boys are less independent.

The original story involves Fenton Hardy kidnapped by drug smugglers, with the boys putting together the pieces of the puzzle involving the "haunted" house on the cliff and hidden tunnels. They rescue their father, though they are almost immediately captured. There's a lot of action, including fist fights but they are believable. Some believe this is the best written novel in the series. The revision has some sloppy writing and makes inexplicable changes in scenes but basically follows the same story.

The HBUHP calls the revision "completely different" but it basically reassembles elements of the original plot in a less coherent way.

The original is more vivid in its scene-setting, and is pretty good at the effect on the town as a series of car thefts continue without a clue. There a nice school scene that's a kind of interlude. Scenes of the Boys in the caves where the thieves have hidden the cars are exciting, even if their handling of "revolvers" comes out of nowhere. The revision again starts with a big action scene--the Hardys have more technology now, like police radios on their motorcycles--but the plot seems more contrived.

In both stories, it's a school friend who is unjustly arrested for the thefts, but the revision adds a buried treasure mystery for some reason. Also the thieves aren't just stealing cars but smuggling in "foreign" arms for "subversives" in the US. Hello, 1950s!

In the original, the Hardy Boys solve the mystery, and catch the bad guys in the act. But in the revision, they gets their butts saved by Dad, who incidentally has "an iron fist." What's up with that? as the Hardys wouldn't say. Also the revision suggests that the Boys' hometown of Bayport is in New England, which is contradicted by several of the originals. They imply and finally say that Bayport is south of New York City.

Introduced by some of the best descriptive writing I’ve read in the series so far, the Hardys and friends take their ice boat to search for a place to go winter camping, and so they explore the small and solitary Cabin Island, but a strange man angrily orders them away. They know the island and its cabin are owned by wealthy Mr. Jefferson, and so are surprised to find a note from him upon their return home, asking them to visit. When they do they see the angry man leaving. From Mr. Jefferson they learn the angry man is named Hanleigh, and is badgering him to sell him the island, but he won’t. The elderly Mr. Jefferson is all smiles—he thanks them for finding his stolen car (in #6 The Shore Road Mystery), rewards them, and agrees to allow them the use of his cabin on the island for their winter outing.

The trip is to begin before Christmas so there is a lovely family scene in which the Hardys celebrate the holiday early so the boys will have both the traditional feast and presents, and their outing. Back on the island they watch Hanleigh in the cabin, measuring the fireplace. He threatens them again but they have the key and he is the trespasser, so he leaves. But they have the start of their mystery: why was he measuring the fireplace? Why is his so fierce about the island?Eventually the boys learn of Mr. Jefferson’s missing collection of priceless stamps, and find a notebook kept by the man suspected of stealing the stamps (it’s the only instance I’ve run across of an actual date: 1917, which the Boys observe was 11 years before.) The notebook contains a coded message, and the mystery goes on from there, with a dramatic climax.

In the revision, Mr. Jefferson’s reward (communicated to them offstage) is permission to camp on Cabin Island, and the promise of a new mystery. When they meet him at his house he asks them to search for his missing grandson, who disappeared around the time that his collection of commemorative medals was stolen. (Why the switch from stamps remains a mystery.) As usual, the incidents crowd together while scenes of ordinary life are dropped or shortened, like the Christmas scene.

Adults (Fenton Hardy and Mr. Jefferson) are also present in the action more often. Both versions involve two minor villains—in the original they are young men, but in the revision they are high school dropouts who hang around the school and make trouble. “Juvenile delinquency” was a catchword of the 1950s. The Hardy Boys page classifies the revision as "Altered."A side note: my copy of the original and of the revision both have the same cover image, and both have a "picture cover," rather than a jacket. My original is evidently part of the reprint series issued in 1962 (and my book apparently was a Christmas gift in 1963, though not to me) and it appears to be the same typeface as the original editions. It also has the same brown flyleaf illustrations as the original brown hardbacks that I remember so well from the public library.

This is my favorite of the originals I've read as an adult, but I don't think that's entirely why I'm contemptuous of the revision, which HBUHP calls "drastically altered."

The original is well-paced and balanced, as each increment of the mystery is pursued with activity, such as the Boys trip to New York City. But most of all, it has a real sense of high school boys doing the investigating, their normal life integrated with the mystery.

It's also a great 1930s story, starting with the opening scene at Bayport's newest innovation, the Automat. Joe is kidnapped, Frank and his chums find him, but that's just the beginning. The brothers impulsively follow a suspect on the train to New York, lose their money to a pickpocket, sleep on park benches safely, prepare to hitchhike back to Bayport and earn a meal by washing dishes at a diner. (The diner owner is right out of a movie by Frank Capra or Preston Sturges.) They get a key clue overhearing a hotel switchboard operator, and learn of the existence of the collect call!

As obsolete and therefore nostalgic as all this seems now, none of it was so arcane in the 1950s when I might have first read this book. The telephone system was basically the same, and I remember going to an automat restaurant in Manhattan in the 1960s.

But the revision dumps pretty much all of it anyway. (Though I thought for sure the revision would drop a key scene of the boys in a biplane that loses power- they have parachutes and go out on a wing to bail out. But the revision makes the plane an antique reconstruction, and the scene happens in a different part of the story.)

Bayport, by the way, in this novel is explicitly said to be located about 200 miles south of New York City, which suggests New Jersey.

The mystery is solved through a combination of legwork, deduction, serendipity and coincidence. (Which fulfills Fenton Hardy's definition of a detective as someone who basically pays attention.) Some may object to the coincidences, such as the clues supplied by the clueless Aunt Gertrude. But it sure makes for a good story that keeps moving forward.

A coincidence puts the Boys in touch with a couple of FBI agents, and so the big finish is more believable with the adult agents doing the shooting and fighting during the capture, though Frank manages to chase and wrestle down the ringleader of the diamond thieves gang. (The Boys relationship with the local police is also better than in previous originals.)

Other elements of the story are kept, but there are inexplicable changes. This time the gang is stealing diamonds and "electronics." (What kind of electronics? Why are they valuable? It doesn't say.) Again another needless and basically useless if not confusing plot element is added, a secret invention.

The revision begins with a completely outlandish fight between the brothers and adult thieves. In general, the revision is haphazard and careless--literally in the sense that it seems to be written by someone who doesn't care. For dialogue that sounds somewhat formal, it substitutes dialogue that sounds entirely wooden. As for updating arcane expressions etc., the revision actually has one of the boys say "Gadzooks!"--a word from the 17th century that barely made it into the 19th.

Finally, let me point out something else that's apparently obsolete. Especially in the originals, I did not find a typo or a grammatical error. These boys books, written quickly and expected to be read by teenagers or younger, and then to disappear, are immaculately edited, copyedited and proofread. So 20th century, right?