|

| Greater Pittsburgh Airport 1960s |

It had always been expensive to fly, and a lot of people were wary of it—too many airplane crashes in the headlines. There were lots of airlines competing and rapidly expanding in the 1960s, but they were regulated, so prices were pretty much the same for all the airlines, and they didn’t change very often.

In 1966, they started offering half fare standby tickets for passengers under age 22. That made a flight cheaper than the train—about $15. (Remember the era-- just the year before the Gizmo had doubled the price of a coke from a nickel to a dime.) Part of the idea was to get a new generation used to traveling by plane, and it pretty much worked.

I left from the Greater Pittsburgh Airport, the largest air terminal in the country when it was built in 1952, just 14 years before. It had a huge Alexander Calder mobile, and a movie theater—after my return flights on later trips, I saw films there while my father drove the 90 minutes to the airport, since I never knew which flight I would get standby.

My destination, O’Hare Airport in Chicago was even newer. It had become Chicago’s main passenger airport only four years before, in 1962. My first flight was probably in a four engine propeller plane. The airlines had started using jets but still mostly for longer distances. When I was growing up, my friends and I spotted planes flying towards Pittsburgh, and learned to distinguish the two engine DC-3s from the four engine DC-6s. Now there were DC-7s, the last big prop planes. I probably made the transition to 707 jets at some point in my standby career.

In those years, TWA had a major presence at O’Hare and a smaller hub in Pittsburgh, so it’s likely that was the airline I took. But if you bought a TWA ticket, that was good for stand-by on Eastern, American, United and Northwest flights—on all the airlines.

Though the prop planes held around a hundred passengers, the average flight left with 40% of the seats empty, so standby was easy, at least at first. Once the college students of America caught on, though, it got harder, especially out of O’Hare. It involved keeping track of upcoming flights and running from airline to airline, gate to gate. But it became the way I traveled to and from Chicago. I still took the train from there to Galesburg.

All I remember about the cabins is that there were just two seats in a row. The cabin was the province of the stewardesses, mostly tall young women in their 20s and early 30s, in official looking uniform jackets and matching skirts. (This was a few years before some smaller airlines began featuring stewardesses in bright colored miniskirts and go-go boots.) They were friendly and had an air of glamour and competence. One of their jobs was to calm and reassure passengers not used to flying, and there were a lot then.

The stewardesses were nice to me. Besides meals and drinks, they distributed small packs of cigarettes. Once one of them surprised me by giving me all the extras in her basket at the end of the flight. I had just turned 20 but they seemed in another category somehow, no matter how close in age they were. Whatever was going on with older businessmen, to me they were the vestal virgins of these temples of the sky.

I may have flown back to Pittsburgh from Chicago the previous spring, but in any case, my first airplane trip was in 1966. The flying itself fascinated me. I always tried to get a window seat. As a child, I pressed myself against the sofa cushions to gaze fixedly out of the picture window at the clouds, imagining myself riding across them, like Hopalong Cassidy. Now I was riding through them, over them, in them...

Then I arrived back at Knox to an unwelcome surprise. I thought I was taking over another student's rental, but his landlord was advised by his lawyer not to rent to me. (Eventually, the other student's lease wound up in court and I spruced up my old suit to give my paltry evidence.)

So I was back at West Berrien while I looked for another place. I found one, and extolled its merits in a letter home: large bedroom and large kitchen, mostly furnished, with stove and refrigerator, not too far from school, and very cheap. I mentioned but glossed over the fact that the bathroom was shared.

What I didn't say was that the apartment was on the second floor, with the bathroom at the foot of the stairs. Using it required latching two doors, and not forgetting to unlatch the one to the first floor apartment, which I assumed belonged to the semi-fierce old landlady. The apartment was in a sagging wood frame building on West Simmons, with my more or less private entrance around the back. The kitchen was indeed pretty large, but the tiled floor bowed a little alarmingly.

The bedroom however was cozy. The landlady's rules included no parties or guests, and though I didn't tempt fate with a social gathering I did have individual visitors, from pretty much the first week. However dubious, it was my first place living on my own.

That fall was the beginning of the trimester system (I don't think they called it that, but in effect that's what it was.) It meant fewer courses in a shorter period of time. For me, that fall was very short of courses. I made yet another attempt at the distribution requirements in language, but it quickly became apparent that I couldn't bluff my way through upper level Spanish. I detected among my fluent classmates a familiarity with spoken Spanish I didn't remotely have. I got the sense that they'd taken years of Spanish in high school, or otherwise learned it. They were starting out at a level I couldn't even aspire to reach by the end of the course. So I dropped it.

That left me with but two courses: Romantic Literature with William Brady, and Modern Fiction with Howard Wilson. William Brady's signature courses were in Shakespeare, but he also taught several other historical English lit courses. Tall, bearded and with a theatrical voice and manner, he was affable and acerbic, and it was hard to tell which was the more sincere aspect.

We were both on the Faculty Committee for Student Affairs, and we had our run-ins this year and the next. Perhaps we wound up friendly enemies. I liked him in spite of myself, and like to think the reverse was also true, but maybe not. For as outspoken as he could be, including public insults, he was not a transparent sort of person.

I remember little of his Romantic Lit course, which surprises me since I'd been drawn to the Romantic poets in high school, and remained interested in that approach as it developed in America. I've since been curious about that period in England and all the relationships of the Byron/Shelley/Keats circle, and both the Romantics revival of attention to nature and their keen interest in science and technology.

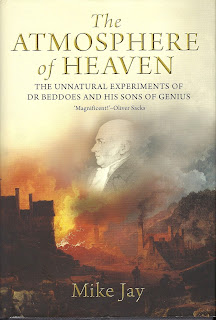

For example, among my books are Nicholas Roe's revisionist biography John Keats (Yale 2012), Daisy Hay's delightful Young Romantics (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2010), and a book that would have been of particular (and subversive) interest in 1966, Mike Jay's The Atmosphere of Heaven (Yale 2009), which tells of the influence of experiments with the mind-altering nitrous oxide on some of the founders of the Romantic movement, and on their key ideas such as the permeability of objective and subjective knowledge. Psychedelic, man.

I don't remember our books for this course. By this time, I had a paperback collection of The Major English Romantic Poets (ed. by William H. Marshall) but I doubt this was the text. All that's survived of this course is a short paper on "Romance and Realism in the Bride of Lammermoor," a novel by Walter Scott I don't remember reading. (Maybe I didn't, but the paper indicates at least a very skillful skim.)

All that I remember is sitting in class one day--a large Old Main classroom-- bargaining with a female student. In exchange for a look at her notes I'd make her laugh. So I scribbled her some verses on Romantic Lit topics in a kind of blues form, based on the Salty Dog Blues. I remember two:

Wordsworth was the Poet Laureate of the Nation

Until he lost his Imagination

Honey, let me be your salty dog

Keats got Shelley, Shelley got Byron,

I got a shirt that don't need ironin'

Honey...etc.

|

| Howard Wilson, spring 1967. Leonard Borden photo. |

I have three levels of confidence in my list of the books we read. The highest level goes to only one--Andre Gide's Lafcadio's Adventures, because I wrote a paper on it that's survived.

The second level of high confidence is based on memory, bolstered in some cases by at least a shred of evidence (such as I still have the book, and can date the purchase to that year.) In this category are A Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man by James Joyce, The Plague by Albert Camus, The Rainbow by D.H. Lawrence and Bread and Wine by Ignazio Silone.

My third level of confidence includes Gide's Strait is the Gate, Camus' The Stranger, William Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom. We probably read Franz Kafka's "The Metamorphosis" and other stories--my list of books from 1966-7 includes the Modern Library Selected Stories of Kafka. I no longer have that volume, replaced by a 1971 edition of Complete Stories.

Perhaps we also read Joyce's stories in Dubliners. Maybe Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. It's possible we also did Confessions of Felix Krull by Thomas Mann, but I don't remember. I also had Mann's Death in Venice and other stories, but I think I got it the year before. Besides I can't imagine we discussed Death in Venice. We simply did not talk about homosexual themes. Beyond these I can think of likely candidates but have no confidence they were included.

I don't know if Camus' nonfiction book, The Myth of Sisyphus was required but I clearly bought it at the same time as his novels. Though it is best remembered for its central myth (pushing the rock up the hill, only to watch it tumble down, pushing it back up in an endless cycle) as a metaphor for life, it functioned also as a primary text in postwar Existentialism, particularly in its definition of the absurd.

Existentialism and the absurd were in part responses to the helplessness, violence and disorder of two world wars and a Depression between them, topped off by the atomic bomb. The 1960s were providing events and pressures that evoked these critiques.

This book also has the most attention-getting first sentence I'd ever read: "There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide." Philosophical or not, suicide was a live issue and anxiety for many of us, and the absurd was all around us, particularly as the Vietnam War intensified other cultural dislocations.

One of the few passage I marked at the time was this: :...in a universe suddenly divested of illusions and lights, man feels an alien, a stranger. His exile is without remedy since he is deprived of the memory of a lost home or the hope of a promised land."

At this point in my young life I hadn't yet recovered the memory of a lost home, and the hope of a promised land was fading fast, as Vietnam and the nuclear age sharpened awareness of the culture's cynical folly, and its plentiful methods of forcing compliance, unto death.

Exile, but artistic exile, was a theme of Joyce's Portrait, the only one of these books I'd already read, which had been important to me with a slightly different emphasis in high school. Now I look at these two books, by Camus and Joyce, and I see much of what I felt about the world and the future, for the rest of my college time and beyond.

I might have found some sense of a lost home in Silone's Bread and Wine, which was set in the Abruzzi region of Italy. But the fact that this was the region where my mother and her family were from had not yet impressed itself on my consciousness. (I've since read Fontamara, the first in his Abruzzi trilogy.)

Of the class, I recall only one moment. It was a small class, that may have met in Wilson's office. He once asked, very cautiously, whether something we were discussing from one of the books was perhaps "blasphemous." I was shocked and offended that the word was even used in an English class, such was my continuing rebellion against my Catholic schooling.

On the other hand...both Lafcadio's Adventure and The Stranger involve the protagonist killing someone, raising various philosophical issues. Gide's protagonist kills an old man as an expression of his freedom. I struggled to follow and to justify their actions based on ideas of existentialism. But I soon rejected it all as bullshit, first just rejecting Gide's justification, but gradually losing interest in existentialism, as well as any excuse for killing people. The sense of the absurd, however, remained and dominated.

Of these books I remember reading Camus' The Stranger and then The Plague (very different narratives.) I remember getting through the Faulkner, but though I could admire the writing, it didn't speak to me. Since grade school, the prevailing image of white southerners I saw was the arrogant racist with a face twisted with hate. (That didn't include southerners I actually knew.) Faulkner's characters didn't interest me. I've still read very little Faulkner; mostly the short stories. Maybe it's time to try again.

I remember reading Lawrence's The Rainbow, alternately slogging through it and being transported by it. Perhaps we also read Women in Love, but if not then, I eventually read it after seeing the famous 1969 film, which ignited a small boom in Lawrence film and TV adaptations, and therefore new paperback editions. I was enthused by Lawrence for awhile (short stories, poems, novels and essays) and by Joyce for longer. But of these specific books, it is only A Portrait of the Artist... that I've read and re-read again over all these years.

That I had only two courses didn't mean I wasn't busy. For one big thing, I had a part in the Knox main stage production of Shakespeare's Macbeth.

At Knox in those days, we did not receive class credit for what was an extensive commitment. Even though my part was relatively small, there were a lot of long rehearsals and performances. I played the Thane of Ross, who is the pivot point of the play. (That's an actor's joke, sort of. In fact, Ross joining the rebellion against Macbeth is a turning point.) A couple of other minor roles were folded into it.

It was directed by theatre professor William Clark, who talked me into it with the same basic argument he used to get me into his theatre history class: if I was going to write plays, I should experience what it's like to go through an actual production, and to be on stage, required to say the words the playwright wrote.

Professor Clark was the department's technical director, and he designed the show. He may have spent time with the principal actors but as I recall the rest of us were left to our own devices, beyond our blocking and cues. We struggled with how to speak the lines--should we be adapting English accents? I remember my fellow thane Harry Contompasis wondering "why is everybody trying to sound like James Mason?"

Memorizing the text was hard enough; figuring out what it meant didn't seem that important. Which is too bad, because Ross has some choice lines:

Alas, poor country,

Almost afraid to know itself! It cannot

Be call'd our mother, but our grave. Where nothing,

But who knows nothing, is once seen to smile;

Where sighs and groans and shrieks that rend the air,

Are made, not mark'd; where violent sorrow seems

A modern ecstasy.

|

| Macbeth program: click to enlarge |

Other than that, we had little to do with the stars: Richard Newman as Macbeth, Valjean McLenighan as Lady Macbeth. I had one big scene with Paul Woldy as Macduff. Most of the time I was hanging out with the other thanes and assorted characters. I don't think I saw David Axelrod at rehearsals but once or twice, before he routinely stole the show as the Porter.

Our costumes were variations on the traditional doublet and hose. I wasn't the only neophyte who was astonished at the blatant artificiality of the props, and the bold lines of makeup that looked absurd in the greenroom mirrors but were standard for making our faces visible to the audience. Such is (or was) the theatre.

We had a number of performances, including some for busloads of high school students. I managed to get through the run with only one real screw-up. My first entrance and speech came very early in the play, but for one performance I was still in the greenroom, leaving Richard Hoover as King Malcolm to pace up and down the stage, waiting for me to announce Macbeth's great victory.

It turned out to be a bit of method acting for me, however, as I tore up the stairs and came on stage running and out of breath, as if Ross ("what a haste looks through his eyes!") is indeed rushing from the battlefield. I believe however this was the moment that Richard started thinking about switching to set and production design.

If I embarrassed myself, no one told me about it, and I did get a couple of compliments: someone whose judgment I respected said that I had one of the better Shakespearean speaking voices, and a female student of my acquaintance thought I looked pretty good in tights.

I can't honestly attribute my participation in this play to my subsequent interest in Shakespeare, but it had to play a part. I saw Romeo and Juliet at Stratford (Ont.) in 1968, and Kevin Kline's Hamlet at the New York Public Theatre in the '80s. But my involvement intensified in the 1990s, when I attended the University of Pittsburgh Shakespeare Festival summer productions, and later when I was a theatre columnist, and got prime seats for productions at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland.

I also became fascinated with film and television productions (Branagh's Much Ado About Nothing remains a favorite), and read history of Shakespeare productions and performances as well as works about Shakespeare and (broadly speaking) critical works. (Favorites among these include W.H. Auden's Shakespeare lectures, Northrup Frye's book of essays, Shakespeare The Thinker by A.D. Nuttall, and Shakespeare's Game by William Gibson, which is also one of the better books on playwriting.) I must have 35 such books now.

And I've also carefully read many of the plays, often in annotated editions. As a result of this reading as well as this seeing, I've written thousands of words on Shakespeare's plays.

And professor Clark turned out to be right about an influence on my playwriting, at least eventually. Also in the 1990s I wrote a play, Young O, which was a prequel to Shakespeare's Othello. This Macbeth production dipped us into a myth-ridden past while we remained otherwise immersed in the demanding 1960s. I wasn't thinking about that when I wrote Young O, but in fact it is set in a mythical stage time that combines 16th century Venice and the 1960s.

But even if this production of Macbeth wasn't the direct start of all that, it did plunge me into the theatrical world of Shakespeare, and created some opening edge of familiarity. I've often found that after reading a difficult text straight through, it suddenly makes much more sense on the second attempt. This production was a little like that.

It also resulted in strengthening friendships with Rick Newman and Valjean, and a new level of acquaintance with others in the production. It also may have helped send me to the hospital. But that's a winter's tale.