I was a little too old for The Mickey Mouse Club television program. All that singing and dancing was girl stuff anyway. But my younger sisters watched it on our only TV set, in the living room. So one afternoon I chanced to see something that caught my eye: a filmed story about two young detectives, small town brothers investigating a mystery, the Hardy Boys.

It was the fall of 1956. The story was told in a series of fifteen minute segments every day. I got involved enough to learn (and remember) the names of the actors: Tim Considine and Tommy Kirk (both of whom would show up in a number of Disney TV and film stories.)

I was 10, and had begun going to the Greensburg public library on my own. Browsing books in the children's room I came upon this now familiar name: the Hardy Boys. Soon I learned to look for the light brown volumes with dark brown titles, and the silhouette of two figures--one with a hat and a scarf--against a jagged background. They must have been among the first books from the library I read all the way through.

In the novels, Frank and Joe Hardy were in their mid to late teens--not early teens as in the Disney series. They rode motorcycles, drove cars and boats and occasionally carried revolvers. They got into fights with adult men, and didn't always win them. But they mostly used their heads, and were old enough to act on their lines of inquiry. They were in some ways the perfect age for me to read about--older boys at the barely imaginable threshold of adulthood, so old enough to be models but not too old to identify with.

Their father, Fenton Hardy, was a highly respected private detective, which also added to the appeal. Their relationship to him and his work, and the way he treated them, were fascinating to boys whose fathers disappeared all day at their unromantic jobs and behind the newspaper in the evening.

The first three Hardy Boys novels were originally published in 1927. The first ten books had been published by 1929, and they then were released at the rate of one a year--for the next 50 years. The author's name emblazoned on all these books was Franklin W. Dixon, though the first 16 and several more later were written by Leslie McFarlane, with other writers between and afterwards. They were writers for hire, with the premise and stories outlined by publisher Edward Stratemeyer, who also came up with Nancy Drew and Tom Swift. He probably also did some rewriting before publication.

There would be new versions of the Hardy Boys over the years since, just as there have been other Hardy Boys on television. There are more than 500 Hardy Boys stories now. But the first 59 volumes are considered the classic series.

Some 36 titles had been published by the time I discovered them. In fact, the first Disney series I saw that adapted the first novel (The Tower Treasure) seems to have borrowed an element from the 36th (The Secret of Pirate Hill.)

I'm not sure how many volumes the Greensburg Library had. I just know I read several, and would eagerly search through what was in the library when I visited. But there was competition--other boys were reading them (and perhaps girls, too, though I didn't know of any) and I knew only one school friend who claimed his older brother actually owned a number of these books. They were only in hardback.

I don't remember which Hardy Boys books I read. I do remember, however, which Hardy Boys book I started writing.

It was "The Creaking Stairs Mystery." I wrote a couple of pages, and was working on them at school in fifth grade. Our regular teacher wasn't there, and a parish priest, Father M., was more or less babysitting. We were supposed to be "working silently" on our own at our desks. He walked up and down the aisles. I was startled when he stopped at my desk and picked up my notebook. He read some of it to himself and then announced the title to the class (getting it wrong.)

He also read out loud a sentence about someone driving a "roadster." He mocked being impressed. I was more than a little sensitive about that word, because in fact I did not know what "roadster" meant. Not knowing precisely what a word meant was not uncommon, either in my reading or in listening to television, or to adults talking, etc. I would know roughly what it meant from context. In this case I knew it meant a kind of car. To me it was a mysterious, romantic word, part of the mysterious world I entered in these books. But to have this ignorance possibly exposed and mocked was embarrassing.

Anyway, as a result of this exposure, I became too self-conscious to continue writing my Hardy Boys story. But I did keep on reading them. I had followed stories told in serial form on television, and loosely so in our school readers, but the Hardy Boys were among the first books I read with a single story developed over its length. These books were deliciously different because I was in charge of reading the story--I could stop at any point, or read chapter after chapter, and just stay in that world.

The books contained funny dialogue and characters, simple descriptions of a party or an afternoon at the beach, but mostly they were exciting, one event or clue, one question, leading to another. I could linger over a scene and ponder it, or go back to something that happened earlier, or re-read something I didn't understand. But as I absorbed the book's world, I read fervently, eager to know what happened next, and to test my impressions and guesses. Though I didn't always manage it, I sustained attention enough to learn the particular delights of doing so.

In 1959, the publishers started revising and shortening the earlier titles, and these versions are the more easily available now. In those books, the roadsters have become jalopies (though more technically roadsters were early two-door convertibles), the "touring cars" are sedans. The revisions were made partly to update such references (and eliminate offensive racial and ethnic stereotypes) so new readers could recognize their world and identify with the young characters.

Later novels with entirely new stories would continue this updating, so in the more recent paperbacks, the Hardy Boys say things like "As if."

The irony of course is that by now a 1959 revision is almost as arcane and unfamiliar as the 1929 original. The later versions in turn will become obsolete. Personally I wouldn't give up the magic that still adheres to the word "roadster."

In fact, I'm glad I read the unrevised originals for a number of reasons. For one thing, in later books the Boys got increasingly sophisticated and unreal, acting more like combinations of Tom Swift and James Bond. This trend started in the 1959 revisions.

According to the indispensable The Hardy Boys unofficial home page, these revisions to the originals are disappointing. "Although the stories were given the same titles and some of the plots remained basically the same, many books were given new plots and are unrecognizable from the originals. Unfortunately, the quality of the writing was nowhere near as high as in the unrevised versions and the resulting stories lost much of their original charm."

A little later, the opinion is more strongly stated: "The quality of the revised stories is generally so far below that of the originals that it can only be considered as an act of literary vandalism."

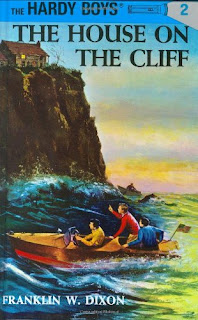

Harsh words, so I compared a few volumes to their originals. The originals were revised over 15 years beginning in 1959. The HBUHP categorizes them as "slightly altered" (generally the later books, which often had been written by the same people doing the revisions) "altered," "drastically altered" and "completely different." I read both versions of The Tower Treasure (#1, marked Altered), The House on the Cliff (#2, Altered),The Shore Road Mystery (#6, Completely Different) and What Happened At Midnight (#10, Drastically Altered.)

|

| Leslie McFarland, the first Hardy Boy |

The literary quality of these books is not high, but McFarlane has a way with dialogue in several of these books, and a humorous and satirical Dickensian flair here and there. The revisions get into action quicker, though those action sequences are often absurd. Even given arcane language, cliches and some awkwardness, there is more life and interest in the originals. The stories are generally more realistic, and better paced.

One notable difference (so others have noticed it, too) is that in the originals, the Hardys relationship to authority, particular to the official police, is strained and even hostile. In the revisions they are much more respectful and the police are much more efficient and cooperative. Maybe it was all that "juvenile delinquency" stuff in the 1950s, plus J. Edgar Hoover and commie subversion that scared the revisers.

The revisions vary in quality from not terrible (The Tower Treasure) to so carelessly written as to be insulting (What Happened At Midnight.) Though I picked up a bunch of the revised novels in a picture cover format at a thrift store, my future reading wherever possible is going to be the originals, especially the McFarlane originals.

In that regard, I've found some used originals with something I never would have seen at the library: dust jackets. (The above photo is not of my collection. I have only two with dust jackets. Needless to say, there are serious collectors.) So here are my observations on the originals versus the revised:

The Tower Treasure (#1)

The original version of this first novel in the series begins with exposition, while the revised starts with an action scene. This appears to be one item of the brief for the revisions--hook the reader with action. This time it works, in others I read the action is absurd by the standards set in the original series--of realism, especially of the Hardy Boys as normal or at least believable boys.

Another item in the brief was to shorten the books to the same length of 180 pages. So what took two chapters and 17 pages in the original is reduced to one chapter and 8 pages in the revised.

Some arcane language in the original is a bit disruptive, though funny, cf. "I'm going to ask these chaps if they saw him pass." But the revision goes further than updating words and eliding the story--it unaccountably adds incidents and characters, to no better effect than the originals. Plus it doesn't actually eliminate all ethnic stereotypes--just the ones people were more sensitive to in 1959.

It isn't long before the losses become obvious. The original has a comic set piece involving a group of farmers; the human comedy is entirely lost in the revision. Similarly a scene involving the small town police chief and his detective is derisively funny. That such scenes reminded me of Dickens is reinforced a few pages later by a reference to a character habitually carrying Dickens' novels (naming three.) (The original also throws in a sly Hamlet reference.)

But the loss of a certain literary quality is more telling in a line Fenton Hardy says to his sons on page 76 of the original, when he tells them they can help "by keeping your eyes and ears open, and by using your wits. That's all there is to detective work."

Later, when the boys accidentally find themselves in a location no one had considered and realize it may be the key to the mystery that has puzzled everyone (including their father), they solve it by finding the treasure. Afterwards they conclude that "The main thing is that we've proved to dad that we know how to keep our eyes and ears open." (209)

The symmetry of these lines more than anything else starts off this series of books. They are entirely absent from the revision.

The revision has the good sense to keep the subplot of the father of one of the Hardy Boys' school friends who is unjustly accused of a crime (a similar situation will be repeated in a subsequent book), even keeping most of the dialogue. But for every arcane line the revision eliminates ("Brace up, old chap," he advised; p67) it seems to lose one of delicate feeling or meaning: "Frank and Joe, their hearts too full for utterance, withdrew softly from the room." (68)

This being the first novel, it has the first instances of official police incompetence, and Fenton Hardy's disdain for the local police. In the revision this is gone, though the comic futility of the chief and his detective Snuff is replaced by a comic Snuff, now an aspiring private detective, and his self-importance, ambition and incompetence.

The climactic scene in the revision suddenly adds a character to increase threat and action (the Disney teleplay has its own version of this character though he appears early, and interestingly represents a seeming friendly but ultimately untrustworthy and violent adult) but it adds little to the scene. The ending of the original is longer and more satisfying.

The House on the Cliff #2

The original story begins with the Hardy Boys and their pals (or "chums") exploring a haunted house (which is also the beginning of the second and final Hardy Boys adventure on Mickey Mouse Club, though that story quickly diverged. It notably took place in mostly one location.) Frank and Joe Hardy discover tools were stolen from their motorcycles, and then witness an attempted murder and rescue the victim from drowning.

The revised version begins with Fenton Hardy letting the boys in on a case in progress. This is another odd trend in the revisions: the boys are less independent.

The original story involves Fenton Hardy kidnapped by drug smugglers, the boys putting together the pieces of the puzzle involving the "haunted" house on the cliff and hidden tunnels. They rescue their father, though they are almost immediately captured. There's a lot of action, including fist fights but they are believable. Some believe this is the best written novel in the series. The revision has some sloppy writing and makes inexplicable changes in scenes but basically follows the same story.

The Shore Road Mystery #6

The HBUHP calls the revision "completely different" but it basically reassembles elements of the original plot in a less coherent way.

The original is more vivid in its scene-setting, and is pretty good at the effect on the town as a series of car thefts continue without a clue. There a nice school scene that's a kind of interlude. Scenes of the Boys in the caves where the thieves have hidden the cars are exciting, even if their handling of "revolvers" comes out of nowhere. The revision again starts with a big action scene--the Hardys have more technology now, like police radios on their motorcycles--but the plot seems more contrived.

In both stories, it's a school friend who is unjustly arrested for the thefts, but the revision adds a buried treasure mystery for some reason. Also the thieves aren't just stealing cars but smuggling in "foreign" arms for "subversives" in the US. Hello, 1950s!

In the original, the Hardy Boys solve the mystery, and catch the bad guys in the act. But in the revision, they gets their butts saved by Dad, who incidentally has "an iron fist." What's up with that? as the Hardys wouldn't say. Also the revision suggests that the Boys' hometown of Bayport is in New England. Which, as we will now see, contradicts one of the originals.

What Happened At Midnight #10

This is my favorite of the originals I've read as an adult, but I don't think that's entirely why I'm contemptuous of the revision, which HBUHP calls "drastically altered."

The original is well-paced and balanced, as each increment of the mystery is pursued with activity, such as the Boys trip to New York City. But most of all, it has a real sense of high school boys doing the investigating, their normal life integrated with the mystery.

It's also a great 1930s story, starting with the opening scene at Bayport's newest innovation, the Automat. Joe is kidnapped, Frank and his chums find him, but that's just the beginning. The brothers impulsively follow a suspect on the train to New York, lose their money to a pickpocket, sleep on park benches safely, prepare to hitchhike back to Bayport and earn a meal by washing dishes at a diner. (The diner owner is right out of a movie by Frank Capra or Preston Sturges.) They get a key clue overhearing a hotel switchboard operator, and learn of the existence of the collect call!

As obsolete and therefore nostalgic as all this seems now, none of it was so arcane in the 1950s when I might have first read this book. The telephone system was basically the same, and I remember going to an automat restaurant in Manhattan in the 1960s.

But the revision dumps pretty much all of it anyway. (Though I thought for sure the revision would drop a key scene of the boys in a biplane that loses power- they have parachutes and go out on a wing to bail out. But the revision makes the plane an antique reconstruction, and the scene happens in a different part of the story.)

Bayport, by the way, in this novel is about 200 miles south of New York City, which suggests New Jersey.

The mystery is solved through a combination of legwork, deduction, serendipity and coincidence. (Which fulfills Fenton Hardy's definition of a detective as someone who basically pays attention.) Some may object to the coincidences, such as the clues supplied by the clueless Aunt Gertrude. But it sure makes for a good story that keeps moving forward.

A coincidence puts the Boys in touch with a couple of FBI agents, and so the big finish is more believable with the adult agents doing the shooting and fighting during the capture, though Frank manages to chase and wrestle down the ringleader of the diamond thieves gang. (The Boys relationship with the local police is also better than in previous originals.)

Other elements of the story are kept, but there are inexplicable changes. This time the gang is stealing diamonds and "electronics." (What kind of electronics? Why are they valuable? It doesn't say.) Again another needless and basically useless if not confusing plot element is added, a secret invention.

The revision begins with a completely outlandish fight between the brothers and adult thieves. In general, the revision is haphazard and careless--literally in the sense that it seems to be written by someone who doesn't care. For dialogue that sounds somewhat formal, it substitutes dialogue that sounds entirely wooden. As for updating arcane expressions etc., the revision actually has one of the boys say "Gadzooks!"--a word from the 17th century that barely made it into the 19th.

Finally, let me point out something else that's apparently obsolete. Especially in the originals, I did not find a typo or a grammatical error. These boys books, written quickly and expected to be read by teenagers or younger and then to disappear, are immaculately edited, copyedited and proofread. So 20th century, right?