On Book Reviewing 2006

Of my published reviews this past year, I was most proud of my piece on Richard Powers' novel, The Echo Makers, although not the review as it was published--as it appears here at Books in Heat. There were editorial changes I wasn't given the opportunity to see in advance that hurt the content a bit, but really (at least for me) hurt the writing. The rhythms are very important.

But I was pleased that when that novel was named a finalist for National Book Award for fiction, my review was linked from the official site. And gratified as well that the review by Margaret Atwood in the New York Review of Books echoed the theme my review started with: that Powers' should have received some major awards by now. And now he has: Powers' The Echo Makers won the 2006 National Book Award for Fiction.

That review was also one of only two published this year that I proposed (the other was Alan Wolfe's Does American Democracy Still Work?, a question that may have been answered in the affirmative by the 2006 election). The others were assignments--I seem to be the go-to guy at the SF Chronicle for science and technology books for a general audience, which is a little baffling considering all the actual science and techology people there are in the Bay Area who could write with more expertise, but maybe that's the point.

The major problem I had as a reviewer of nonfiction this year is the absense of indexes in bound galleys. The Chronicle wants to publish reviews very close to the book's pub date, which means reading the bound galleys that are available a few months ahead of time. No longer marked-up pages bound between generic-looking soft covers, galleys these days are cleaned-up versions packaged pretty much as they will appear in hardback. The photos don't look as good, but non-fiction books often include the author's notes and bibliography. What they don't include is precisely what reviewers--or this one anyway-- would find very useful: the index.

As I read the book I come upon passages that seem key and/or quotable, and I mark or note those. But I can't mark the whole book, and I don't always know until further along, or even until I've finished the book, which passages are going to be important, or memorable. An index would help me find what I'm looking for, when it comes time to write the review.

I don't see a technical or cost problem--if my computer can do an index on command, I expect theirs can. I don't know why they don't include an index, even if it's changed to reflect changes for publication. Maybe it's as crass as discouraging reviewers from selling the galleys to bookstores. But it's my most fervent plea for 2007--give me your indexes, for the sake of my tired poor eyes.

Friday, December 22, 2006

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

The Emotion Machine

Commonsense Thinking, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of the Human Mind

By Marvin Minsky

SIMON & SCHUSTER; 387 Pages; $26

Science may begin with wonder and strives ultimately for understanding, but as a practical matter, science is interested in how to do things. Physics formulated a few simple laws (governing how falling bodies behave, for example), which enabled engineering and technology to develop.

So when some scientists set out to create intelligent machines -- "machines to mimic our minds" -- Marvin Minsky writes, they looked for simple laws that govern how our brains work. They didn't find them, he argues, because our brains are "complicated machinery" and we need "to find more complicated ways to explain our most familiar mental events." Humans adapt to different environments and situations because our brains are resourceful -- we have lots of different ways to solve problems, and if one doesn't work, we can switch to another. This book is about what Minsky believes those processes are.

continued at the San Francisco Chronicle Book Review

Commonsense Thinking, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of the Human Mind

By Marvin Minsky

SIMON & SCHUSTER; 387 Pages; $26

Science may begin with wonder and strives ultimately for understanding, but as a practical matter, science is interested in how to do things. Physics formulated a few simple laws (governing how falling bodies behave, for example), which enabled engineering and technology to develop.

So when some scientists set out to create intelligent machines -- "machines to mimic our minds" -- Marvin Minsky writes, they looked for simple laws that govern how our brains work. They didn't find them, he argues, because our brains are "complicated machinery" and we need "to find more complicated ways to explain our most familiar mental events." Humans adapt to different environments and situations because our brains are resourceful -- we have lots of different ways to solve problems, and if one doesn't work, we can switch to another. This book is about what Minsky believes those processes are.

continued at the San Francisco Chronicle Book Review

Monday, October 23, 2006

A Trinity from Trinity

Barbara Ras is one of those friends it is sometimes hard for me to believe I haven't actually met. I may have spoken to her once on the phone, but almost our entire relationship over the past 8 or 9 years has been through emails and through our respective writing.

Barbara was the editor in chief at University of Georgia Press back then, and has since taken over and, as far as I can tell, essentially transformed Trinity University Press. Trinity specializes in her two chief areas of interests, the natural world and literature, as well as specifically Texan topics (it's in San Antonio.)

She is also a widely published and award-winning poet, and she recently sent me her new collection, One Hidden Stuff (Penguin). It reflects those Trinity concerns as well, in the context of her life and our times. She works with long lines, so it helps that she has a sure sense of rhythm. As a reader as well as a writer, rhythm is very important to me, in prose, in dialogue and especially in poetry. Appropriately then, the book begins with "Rhapsody Today." The first lines flow melodically, until a slight pause in the fourth for a fine effect, a fawn on gawky legs with "some leftover dazed grace," and so we see the fawn's motion standing still.

My current favorites among these enticing poems come towards the end of the book, like "Late Summer Night" which seems to have been written soon after her move to Texas, and reminds me of the surprising dislocation I felt after my latest move, to California. "Sometimes Like the Ocean" makes poetry from the poetics of a dream, and "Elsewhere" merges the horror of distant war with more personal loss, within the theme of motherhood. "Our Flowers" seems to contain all the elements of previous poems in the book, and contains a favorite line: " Failure is such a beautiful word for something/lousy..." I'm glad for the opportunity to read these poems, and to have them around to read again, and I'll bet you will be, too.

As it happened, two books from Trinity Press itself arrived soon after. In A Special Light by Elroy Bode is a book of essays heavy on reminicence and observation of the Texas hill country. That's not a landscape that frankly attracts me much, but I found myself beguiled by Bode's prose and his memories of times if not places we've shared. The conversational style is most obvious in the very short chapters but its flow, and Bode's way with the particular, can keep you reading despite yourself, or the call of supposedly more urgent matters.

The mail occasionally brings a treasure, and that's the word for Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape, edited by Barry Lopez. It's a kind of dictionary of terms pertaining to the landscape, with definitions by a number of distinguished writers, including William Kittredge, Greta Ehrlich, Bill McKibben, Barbara Kingsolver, Linda Hogan and Charles Frazier. Some 45 writers participated, in a three year first draft process with managing editor Debra Gwartney, and another year with Lopez.

My first thought was quite practical--at last a companion to reading the likes of Jim Harrison, only instead of a few line definition of "swale"in the standard dictionary, here is a full page--with history, examples and an illustration! But besides ignoramuses like me, I'm sure people who know these words from familiarity with what they denote will find something in these definitions to light them up as well. There are regional terms and words from folklore that have fallen out of use, plus examples of their use from literary works.

Start at any page and there's something interesting. Barbara Kingsolver provides a precise definition of "derramadero" right after she defines "derelict land" as "Land that has been used, ruined, and consequently abandoned by humans is peculiarly described as derelict--as if the land itself had become careless of its duties." The San Francisco Chronicle review goes into more detail. This volume becomes an instant reference resource, while itself being a connection to place and a portrait of the American landscape.

Barbara Ras is one of those friends it is sometimes hard for me to believe I haven't actually met. I may have spoken to her once on the phone, but almost our entire relationship over the past 8 or 9 years has been through emails and through our respective writing.

Barbara was the editor in chief at University of Georgia Press back then, and has since taken over and, as far as I can tell, essentially transformed Trinity University Press. Trinity specializes in her two chief areas of interests, the natural world and literature, as well as specifically Texan topics (it's in San Antonio.)

She is also a widely published and award-winning poet, and she recently sent me her new collection, One Hidden Stuff (Penguin). It reflects those Trinity concerns as well, in the context of her life and our times. She works with long lines, so it helps that she has a sure sense of rhythm. As a reader as well as a writer, rhythm is very important to me, in prose, in dialogue and especially in poetry. Appropriately then, the book begins with "Rhapsody Today." The first lines flow melodically, until a slight pause in the fourth for a fine effect, a fawn on gawky legs with "some leftover dazed grace," and so we see the fawn's motion standing still.

My current favorites among these enticing poems come towards the end of the book, like "Late Summer Night" which seems to have been written soon after her move to Texas, and reminds me of the surprising dislocation I felt after my latest move, to California. "Sometimes Like the Ocean" makes poetry from the poetics of a dream, and "Elsewhere" merges the horror of distant war with more personal loss, within the theme of motherhood. "Our Flowers" seems to contain all the elements of previous poems in the book, and contains a favorite line: " Failure is such a beautiful word for something/lousy..." I'm glad for the opportunity to read these poems, and to have them around to read again, and I'll bet you will be, too.

As it happened, two books from Trinity Press itself arrived soon after. In A Special Light by Elroy Bode is a book of essays heavy on reminicence and observation of the Texas hill country. That's not a landscape that frankly attracts me much, but I found myself beguiled by Bode's prose and his memories of times if not places we've shared. The conversational style is most obvious in the very short chapters but its flow, and Bode's way with the particular, can keep you reading despite yourself, or the call of supposedly more urgent matters.

The mail occasionally brings a treasure, and that's the word for Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape, edited by Barry Lopez. It's a kind of dictionary of terms pertaining to the landscape, with definitions by a number of distinguished writers, including William Kittredge, Greta Ehrlich, Bill McKibben, Barbara Kingsolver, Linda Hogan and Charles Frazier. Some 45 writers participated, in a three year first draft process with managing editor Debra Gwartney, and another year with Lopez.

My first thought was quite practical--at last a companion to reading the likes of Jim Harrison, only instead of a few line definition of "swale"in the standard dictionary, here is a full page--with history, examples and an illustration! But besides ignoramuses like me, I'm sure people who know these words from familiarity with what they denote will find something in these definitions to light them up as well. There are regional terms and words from folklore that have fallen out of use, plus examples of their use from literary works.

Start at any page and there's something interesting. Barbara Kingsolver provides a precise definition of "derramadero" right after she defines "derelict land" as "Land that has been used, ruined, and consequently abandoned by humans is peculiarly described as derelict--as if the land itself had become careless of its duties." The San Francisco Chronicle review goes into more detail. This volume becomes an instant reference resource, while itself being a connection to place and a portrait of the American landscape.

Saturday, October 07, 2006

Everything Dances

by William S. Kowinski

A different version of this review appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle.

The Echo Maker

By Richard Powers

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 464 PAGES; $25.

That Richard Powers did not win the Pulitzer for his 2003 novel, The Time of Our Singing, or the National Book Award for Plowing the Dark (2000) astonishes me. He’s generally considered to be among America’s foremost novelists, but as an academic in Illinois, he’s overlooked in Flyoverland. Perhaps a New York character in his new novel will help.

As publishing converts to the condition of Hollywood, I imagine this book being pitched as “Oliver Sacks meets Aldo Leopold on CSI.” Gerald Weber, a Sacks-like neuroscientist and essayist in New York (Sacks wrote the bestsellers, Anticipations and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat), is drawn to Kearney, Nebraska to meet Mark, a man who mistakes his sister for an actress pretending to be his sister. Mark is a 27-year-old worker in a slaughterhouse whose car crashes on an empty highway. Desperate to help him, his older sister Karin contacts Weber, who can’t resist the chance to observe someone with this very rare disorder caused by the accident.

Mark valiantly improvises a version of reality to account for his persistent feeling that he’s trapped in someone else’s dream, which Powers renders with a convincing seamlessness (including a few neurologically-justified Joycean leaps). Mark’s fierce insistence on his half-constructed delusions begins to affect Karin and Weber, prodding their own self-doubts. They all meet and are affected by Barbara, a mysterious nurse’s aide. Meanwhile, Karin renews relationships with two old flames who turn out to be on opposite sides of a dispute affecting what is becoming the town’s biggest industry: the annual presence of migrating sandhill cranes, and the tourists they attract.

Traditional mysteries propel the narrative: what happened on that dark stretch of highway? Mark can’t remember the accident, the police find three sets of tire tracks, but someone who was apparently there has left a note by Mark’s bedside, and vanished. Who made the other tire tracks and why? Who called in the accident, and who wrote the enigmatic note? (And for the whodunit fans in each of us, all is revealed, with not-quite the mystic symmetry of the conclusion to Powers’ last two novels.) There are also the familiar novelistic conundrums of personality and relationships: What are the true motives of Karin’s lovers, and which will she choose? Who is Barbara—cipher, saint or something else? Will Mark recover, and will anyone else?

But of course this is a Richard Powers novel—the writer who has previously dealt with relationships of image and time, molecular biology and Bach, human and artificial intelligence, the corporate body and the human body, race and culture, terror and magic. So there are deeper mysteries as well, prompted by mind science and crucial in our lives: what really is the relationship of memories to exterior events? Do we construct stories to explain reality, or recollect reality according to the stories we tell ourselves? What indeed is a person-- what identity holds together beings who are “every second being born?”

For all their explorations of ideas, Powers novels are always grounded in place and time. This one occurs just as the current Iraq war is beginning, but this well-storied place is even more significant: the Nebraska of fiction from Willa Cather through Jim Harrison, Ted Kooser’s poetry and essays by John Janovy and other naturalists. Powers finds a contemporary part of it to make his own, in the urbanized, small-city landscape, with brief but significant forays into the realm of the cranes.

The cranes are “…the oldest flying things on earth, one stutter-step away from pterodactyls.” Half a million fly from Mexico and the southwest to stop for the last weeks of winter along the Platte river, before continuing to the Arctic. Partly because of the apparent speech of their calls, the cranes have symbolic power: Powers notes that the name of one Native American tribe’s crane clan translates as the Echo Makers. Echoes reflect, refract, double and distort. Description is a kind of echo, affected by the physics of time, distance and substance, as is mental reflection and perception itself, in individuals, society and the species. Emotion and instinct, personal history and parental echoes are part of the ongoing song.

But the cranes have more than metaphorical weight—their plight signals a physical crisis. Daniel, Karin’s environmentalist lover, notes that the greater number of cranes coming to Kearney actually mean that their days are numbered—this is one of the last habitats left for them to gather along their migratory route. Like the last part of Plowing the Dark, there’s a definite apocalyptic feel to this novel, intimations of an imminent and unstoppable finality, and of people dealing with this fragility in their individual ways, including those who listen to what these greater forces ask of them.

The mysteries of perception and cognition, of normality and dysfunction, of reality and dream--all of them are louder echoes of the most pressing mystery that Powers begins to deal with here: the neglected relationship of human beings with the rest of nature, as well as their own. Recalling a Native American legend, he writes “When animals and people all spoke the same language, crane calls said exactly what they meant. Now we live in unclear echoes.” And then he quotes a bit of scripture that may have inspired more than one of his books: “The turtledove, swallow, and crane keep the time of their coming…”

Powers’ prose is sensual and musical; he writes mostly convincing characters, and he structures story to meet a reader’s needs as well as for more subtle purposes. So even though this is a novel with multiple resonance, it’s also readable in the airplane’s stale oxygen drone. But beware: this novel will echo beyond the airport. It may even suggest that the echo of reality is all that we have, and to that music we improvise our lives with as much grace as we can. Or as Barbara says to Weber as they observe the cranes at dawn: everything dances.

by William S. Kowinski

A different version of this review appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle.

The Echo Maker

By Richard Powers

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 464 PAGES; $25.

That Richard Powers did not win the Pulitzer for his 2003 novel, The Time of Our Singing, or the National Book Award for Plowing the Dark (2000) astonishes me. He’s generally considered to be among America’s foremost novelists, but as an academic in Illinois, he’s overlooked in Flyoverland. Perhaps a New York character in his new novel will help.

As publishing converts to the condition of Hollywood, I imagine this book being pitched as “Oliver Sacks meets Aldo Leopold on CSI.” Gerald Weber, a Sacks-like neuroscientist and essayist in New York (Sacks wrote the bestsellers, Anticipations and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat), is drawn to Kearney, Nebraska to meet Mark, a man who mistakes his sister for an actress pretending to be his sister. Mark is a 27-year-old worker in a slaughterhouse whose car crashes on an empty highway. Desperate to help him, his older sister Karin contacts Weber, who can’t resist the chance to observe someone with this very rare disorder caused by the accident.

Mark valiantly improvises a version of reality to account for his persistent feeling that he’s trapped in someone else’s dream, which Powers renders with a convincing seamlessness (including a few neurologically-justified Joycean leaps). Mark’s fierce insistence on his half-constructed delusions begins to affect Karin and Weber, prodding their own self-doubts. They all meet and are affected by Barbara, a mysterious nurse’s aide. Meanwhile, Karin renews relationships with two old flames who turn out to be on opposite sides of a dispute affecting what is becoming the town’s biggest industry: the annual presence of migrating sandhill cranes, and the tourists they attract.

Traditional mysteries propel the narrative: what happened on that dark stretch of highway? Mark can’t remember the accident, the police find three sets of tire tracks, but someone who was apparently there has left a note by Mark’s bedside, and vanished. Who made the other tire tracks and why? Who called in the accident, and who wrote the enigmatic note? (And for the whodunit fans in each of us, all is revealed, with not-quite the mystic symmetry of the conclusion to Powers’ last two novels.) There are also the familiar novelistic conundrums of personality and relationships: What are the true motives of Karin’s lovers, and which will she choose? Who is Barbara—cipher, saint or something else? Will Mark recover, and will anyone else?

But of course this is a Richard Powers novel—the writer who has previously dealt with relationships of image and time, molecular biology and Bach, human and artificial intelligence, the corporate body and the human body, race and culture, terror and magic. So there are deeper mysteries as well, prompted by mind science and crucial in our lives: what really is the relationship of memories to exterior events? Do we construct stories to explain reality, or recollect reality according to the stories we tell ourselves? What indeed is a person-- what identity holds together beings who are “every second being born?”

For all their explorations of ideas, Powers novels are always grounded in place and time. This one occurs just as the current Iraq war is beginning, but this well-storied place is even more significant: the Nebraska of fiction from Willa Cather through Jim Harrison, Ted Kooser’s poetry and essays by John Janovy and other naturalists. Powers finds a contemporary part of it to make his own, in the urbanized, small-city landscape, with brief but significant forays into the realm of the cranes.

The cranes are “…the oldest flying things on earth, one stutter-step away from pterodactyls.” Half a million fly from Mexico and the southwest to stop for the last weeks of winter along the Platte river, before continuing to the Arctic. Partly because of the apparent speech of their calls, the cranes have symbolic power: Powers notes that the name of one Native American tribe’s crane clan translates as the Echo Makers. Echoes reflect, refract, double and distort. Description is a kind of echo, affected by the physics of time, distance and substance, as is mental reflection and perception itself, in individuals, society and the species. Emotion and instinct, personal history and parental echoes are part of the ongoing song.

But the cranes have more than metaphorical weight—their plight signals a physical crisis. Daniel, Karin’s environmentalist lover, notes that the greater number of cranes coming to Kearney actually mean that their days are numbered—this is one of the last habitats left for them to gather along their migratory route. Like the last part of Plowing the Dark, there’s a definite apocalyptic feel to this novel, intimations of an imminent and unstoppable finality, and of people dealing with this fragility in their individual ways, including those who listen to what these greater forces ask of them.

The mysteries of perception and cognition, of normality and dysfunction, of reality and dream--all of them are louder echoes of the most pressing mystery that Powers begins to deal with here: the neglected relationship of human beings with the rest of nature, as well as their own. Recalling a Native American legend, he writes “When animals and people all spoke the same language, crane calls said exactly what they meant. Now we live in unclear echoes.” And then he quotes a bit of scripture that may have inspired more than one of his books: “The turtledove, swallow, and crane keep the time of their coming…”

Powers’ prose is sensual and musical; he writes mostly convincing characters, and he structures story to meet a reader’s needs as well as for more subtle purposes. So even though this is a novel with multiple resonance, it’s also readable in the airplane’s stale oxygen drone. But beware: this novel will echo beyond the airport. It may even suggest that the echo of reality is all that we have, and to that music we improvise our lives with as much grace as we can. Or as Barbara says to Weber as they observe the cranes at dawn: everything dances.

Monday, September 18, 2006

Democracy In Question

Does American Democracy Still Work?

By Alan Wolfe

Yale University Press

Whose Freedom?

The Battle Over America's Most Important Idea

By George Lakoff

Farrar, Straus & Giroux

If you are left aghast and amazed by politics and government today, these two books are for you. There are plenty of screeds and exposes on the details, but Boston College political scientist Alan Wolfe and UC Berkeley professor of linguistics George Lakoff concentrate on the bigger picture of what is happening and why.

This is not your grandfather’s democracy, they say; it’s not even your father’s. Most Americans over 30 -- especially liberals and moderates -- who formed their impressions of political institutions and the political dialogue before, say, 1984, are in for a rude awakening.

Continued at the San Francisco Chronicle Book Review

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

Technology Matters: Questions to Live With

by David E. Nye

The MIT Press

Technology, historian David Nye writes, is a very recent word, in the sense we use it today--perhaps routinely used only since the 1930s. But what our machines are doing to us has been a deep concern ever since there were machines. Leo Marx wrote beautifully about its impact on the thinking of American writers like Hawthorne and Thoreau in The Machine in the Garden. (Nye cites the author though not this work.) Machine dreams and machine nightmares became central to a lot of English literature from Mary Shelley through Dickens to H.G. Wells, and into the 20th century.

David Nye writes clearly and succinctly about many of the issues that technology raises, from an early 21st century historical perspective. He examines the relationship of technology to nature, cultural diversity, economics and human consciousness and intelligence. You may not always agree with his point of view, but he provides a sound basis for discussion, as well as a fascinating reading experience.

This is a book for more than a season. It goes on my shelf of books on this subject I will return to and refer to for years.

by David E. Nye

The MIT Press

Technology, historian David Nye writes, is a very recent word, in the sense we use it today--perhaps routinely used only since the 1930s. But what our machines are doing to us has been a deep concern ever since there were machines. Leo Marx wrote beautifully about its impact on the thinking of American writers like Hawthorne and Thoreau in The Machine in the Garden. (Nye cites the author though not this work.) Machine dreams and machine nightmares became central to a lot of English literature from Mary Shelley through Dickens to H.G. Wells, and into the 20th century.

David Nye writes clearly and succinctly about many of the issues that technology raises, from an early 21st century historical perspective. He examines the relationship of technology to nature, cultural diversity, economics and human consciousness and intelligence. You may not always agree with his point of view, but he provides a sound basis for discussion, as well as a fascinating reading experience.

This is a book for more than a season. It goes on my shelf of books on this subject I will return to and refer to for years.

Monday, June 12, 2006

Two for the Ages

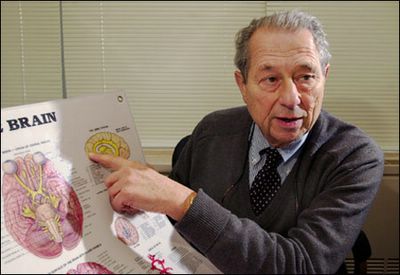

This spring , Yale University Press has published summary works by two distinguished Americans in different fields that address attitudes and actions forming our common world : the famed psychologist and writer Jerome Kagan, and the veteran expert on public opinion and social values research, Daniel Yankelovich. Both books are of special interest to their disciplines but in this era of boundlessly bounded expertise, both are of immense value to a wider readership. This relevance reflects the careers and lifelong concerns of both authors to relate their work to the general welfare, and to the major public dialogues of their times.

Jerome Kagan’s An Argument For Mind is structured around autobiography, beginning with his graduate work in psychology in 1950. Kagan describes his own state of mind and views, as well as the state of psychology in the context of relevant public events and dominant ideas of the time. Without jargon or smothering detail, he creates a generous and thoughtful history of the discipline over the past half century.

Psychology is a field where battle lines have long been drawn between those who rely strictly on experiments and statistics and other data, and whose therapies usually involve drugs, and those whose observations are more general and contextual, and whose therapies involve “talking” and applying concepts in active partnership with patients. There’s conflict between those who emphasize environmental factors, and prescribe cognitive or behavioral therapies as well as particular parenting procedures, and those who emphasize genetics and brain chemistry, prescribing drugs and other methods of manipulation and control.

Kagan not only uses insights and techniques from all camps, based on his own researches, but further relates his observations in this book to characters and situations in literature, movies or shared popular culture, accessible to all of us.

Kagan is renowned for his work in developmental psychology and how children learn. He is not afraid to use concepts such as virtue and morality in describing aspects of his findings and conclusions, without getting mired in judgments. This willingness to use broadly known concepts also contributes to making this book more accessible and relevant to public debate as well as personal insight.

In his concluding chapter, Kagan writes about the limitations and the relevance of biology to psychology, of (among other things) brain to mind. In writing about these issues as well as others of general concern in a field that continues to have vast direct and indirect importance to all of us, he displays a quality much missed since the passing of the founding giants of modern psychology: wisdom. You (like me) may not agree with every conclusion, but Kagan writes with the authority, clarity and generosity that gives us the information and context to grasp the issues and make up our own minds.

text continues after photo

This spring , Yale University Press has published summary works by two distinguished Americans in different fields that address attitudes and actions forming our common world : the famed psychologist and writer Jerome Kagan, and the veteran expert on public opinion and social values research, Daniel Yankelovich. Both books are of special interest to their disciplines but in this era of boundlessly bounded expertise, both are of immense value to a wider readership. This relevance reflects the careers and lifelong concerns of both authors to relate their work to the general welfare, and to the major public dialogues of their times.

Jerome Kagan’s An Argument For Mind is structured around autobiography, beginning with his graduate work in psychology in 1950. Kagan describes his own state of mind and views, as well as the state of psychology in the context of relevant public events and dominant ideas of the time. Without jargon or smothering detail, he creates a generous and thoughtful history of the discipline over the past half century.

Psychology is a field where battle lines have long been drawn between those who rely strictly on experiments and statistics and other data, and whose therapies usually involve drugs, and those whose observations are more general and contextual, and whose therapies involve “talking” and applying concepts in active partnership with patients. There’s conflict between those who emphasize environmental factors, and prescribe cognitive or behavioral therapies as well as particular parenting procedures, and those who emphasize genetics and brain chemistry, prescribing drugs and other methods of manipulation and control.

Kagan not only uses insights and techniques from all camps, based on his own researches, but further relates his observations in this book to characters and situations in literature, movies or shared popular culture, accessible to all of us.

Kagan is renowned for his work in developmental psychology and how children learn. He is not afraid to use concepts such as virtue and morality in describing aspects of his findings and conclusions, without getting mired in judgments. This willingness to use broadly known concepts also contributes to making this book more accessible and relevant to public debate as well as personal insight.

In his concluding chapter, Kagan writes about the limitations and the relevance of biology to psychology, of (among other things) brain to mind. In writing about these issues as well as others of general concern in a field that continues to have vast direct and indirect importance to all of us, he displays a quality much missed since the passing of the founding giants of modern psychology: wisdom. You (like me) may not agree with every conclusion, but Kagan writes with the authority, clarity and generosity that gives us the information and context to grasp the issues and make up our own minds.

text continues after photo

Applying conclusions backed up by factual findings also characterizes Profit With Honor: The New Stage of Market Capitalism by Daniel Yankelovich. Though his name might be most familiar as a pollster, he has also been involved in public policy (as chair of Public Agenda) and education (Viewpoint Learning) as well as serving on boards of corporations in various industries.

He begins with recent business scandals, and the inadequacy of new regulations and enforcement. We need “normative climate that encourages compliance with laws and regulations,” and “History shows you cannot fight bad norms solely with laws.”

But even beyond illegal activity, he argues, the so-called magic of the marketplace won’t produce ethical results to benefit society. History also shows that market economies “vary from era to era and from culture to culture. Their inherent nature is far less clear-cut than either their advocates or their opponents presuppose.”

In the second half of this relatively short book, Yankelovich describes his vision of “stewardship ethics” and how in practical terms they might work, for the benefit of society and individual businesses, and their stockholders. The vision of businesses operating from an attitude of stewardship, looking for the long-term benefit of society and the corporation, is in some ways radical, yet it is a practical way to respond to many problems of present and near-future reality that both societies and businesses will necessarily face, including the major challenges of energy and environment.

“The most creative challenge of stewardship ethics is to learn how to make profitability and society’s interest more compatible.” That’s saying a mouthful, and there will be many skeptics on all sides of these issues. But if this is the culmination of Yankelovich’s work, it could be a valuable legacy. He believes such a pervasive change in operational attitude must come from CEOs, and he’s using a lifetime of credibility to make his case. It is an act of courage, and that, along with that credibility and his career, means this book deserves a hearing. But then, just the merits of the case he builds in this book call for serious attention. Something like stewardship ethics may well be required not only for a better future, but to prevent a far worse one.

He begins with recent business scandals, and the inadequacy of new regulations and enforcement. We need “normative climate that encourages compliance with laws and regulations,” and “History shows you cannot fight bad norms solely with laws.”

But even beyond illegal activity, he argues, the so-called magic of the marketplace won’t produce ethical results to benefit society. History also shows that market economies “vary from era to era and from culture to culture. Their inherent nature is far less clear-cut than either their advocates or their opponents presuppose.”

In the second half of this relatively short book, Yankelovich describes his vision of “stewardship ethics” and how in practical terms they might work, for the benefit of society and individual businesses, and their stockholders. The vision of businesses operating from an attitude of stewardship, looking for the long-term benefit of society and the corporation, is in some ways radical, yet it is a practical way to respond to many problems of present and near-future reality that both societies and businesses will necessarily face, including the major challenges of energy and environment.

“The most creative challenge of stewardship ethics is to learn how to make profitability and society’s interest more compatible.” That’s saying a mouthful, and there will be many skeptics on all sides of these issues. But if this is the culmination of Yankelovich’s work, it could be a valuable legacy. He believes such a pervasive change in operational attitude must come from CEOs, and he’s using a lifetime of credibility to make his case. It is an act of courage, and that, along with that credibility and his career, means this book deserves a hearing. But then, just the merits of the case he builds in this book call for serious attention. Something like stewardship ethics may well be required not only for a better future, but to prevent a far worse one.

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

Springing Forth: Notes on Four

“So many books, so little time” says a sweatshirt I sometimes wear in public, and it elicits rueful nods and grimaces. Despite the tons of bad books published every season, there are still more good books coming out than any one person can read. Here are a few that may have got away from the attention of many reviewers and potential readers this spring.

Novel Beginnings: Experiments in Eighteenth Century English Fiction by Patricia M. Spacks (Yale) is readable scholarship that fills a gap for readers curious about early novels and how the novel developed. The English novel was born in the 18th century as a popular form that mixed drama and epic with such everyday forms as sermons, accounts of travels, journals and journalism, in an era of expanding literacy. Every early novel was an experiment but many approaches got lost in the rush to a mainstream form. Spacks looks at novels of adventure, development, consciousness, sentiment, manners, gothic fiction and political novels, ending with a lengthy consideration of Tristam Shandy. This book is filled with rich delights and delightful possibilities.

Defiant Gardens: Making Gardens in Wartime by Kenneth I. Helphand (Trinity University Press). From a French soldier’s flower bed on the Western Front in the Great War to an American soldier’s bed of grass near Baghdad in 2004, Helphand considers the impulse and result of creating gardens in the midst of mechanized violence and terror. Growing life in the shadow of death extends to ghetto gardens and gardens in POW camps in World War II. This is a unique history, with a section (“Digging Deeper”) that explores meaning. Nature and beauty versus the worst of machines and human ugliness are some of the stark contrasts that inhabit these human stories. With black and white photographs.

Conversation: A History of A Declining Art by Stephen Miller (Yale) is a history (with particular reference to the “age of conversation” and 18th century British coffeehouses) with a point. In his latter chapters, Miller decries the decline of conversation in an age of cell phones and “anger communities.” But he doesn’t define good conversation as humorless—wit and raillery were once essential. It can be, as Virginia Woolf maintained, a result of “showing off.” But if we can’t converse with Cicero, Montaigne and Defoe, we can at least read about their conversational expectations. I don’t endorse all of Miller’s conclusions, especially about recent decades, but at least it’s a conversation-starter.

Bedrock: Writers on the Wonders of Geology, Edited by Laurel E. Savoy, Eldridge M Moores, and Judith E. Moores (Trinity University Press.) Our modern sense of time and change began with geology. Rock strata revealed by mining and canal digging, along with fossils discovered in the same digs, led to an expanded sense of the earth’s age, and inspired Darwin in his consideration of biological evolution. This anthology takes a very wide view of the subject, including excerpts from writers like Mark Twain, James Joyce, Lucille Clifton and Michael Ondaatje as well as Darwin, Loren Eiseley, John McPhee and Paul Shepard in sections titled “Of Rock and Stone,” “Deep Time,” “Faults, Earthquakes and Tsunamis,” “Volcanoes and Eruptions” (where Ursula Le Guin appears along with Pliny the Younger), “On Mountains and Highlands,” Rivers to the Sea,” “The Work of Ice,” “Wind and Desert” and “Living on Earth.” These pieces add up to senses of where geologic matters fit into the web of life, including how humans interact with these objects and forces—neither animal or vegetable but in some sense, so many clearly feel, alive—in many times and cultures.

“So many books, so little time” says a sweatshirt I sometimes wear in public, and it elicits rueful nods and grimaces. Despite the tons of bad books published every season, there are still more good books coming out than any one person can read. Here are a few that may have got away from the attention of many reviewers and potential readers this spring.

Novel Beginnings: Experiments in Eighteenth Century English Fiction by Patricia M. Spacks (Yale) is readable scholarship that fills a gap for readers curious about early novels and how the novel developed. The English novel was born in the 18th century as a popular form that mixed drama and epic with such everyday forms as sermons, accounts of travels, journals and journalism, in an era of expanding literacy. Every early novel was an experiment but many approaches got lost in the rush to a mainstream form. Spacks looks at novels of adventure, development, consciousness, sentiment, manners, gothic fiction and political novels, ending with a lengthy consideration of Tristam Shandy. This book is filled with rich delights and delightful possibilities.

Defiant Gardens: Making Gardens in Wartime by Kenneth I. Helphand (Trinity University Press). From a French soldier’s flower bed on the Western Front in the Great War to an American soldier’s bed of grass near Baghdad in 2004, Helphand considers the impulse and result of creating gardens in the midst of mechanized violence and terror. Growing life in the shadow of death extends to ghetto gardens and gardens in POW camps in World War II. This is a unique history, with a section (“Digging Deeper”) that explores meaning. Nature and beauty versus the worst of machines and human ugliness are some of the stark contrasts that inhabit these human stories. With black and white photographs.

Conversation: A History of A Declining Art by Stephen Miller (Yale) is a history (with particular reference to the “age of conversation” and 18th century British coffeehouses) with a point. In his latter chapters, Miller decries the decline of conversation in an age of cell phones and “anger communities.” But he doesn’t define good conversation as humorless—wit and raillery were once essential. It can be, as Virginia Woolf maintained, a result of “showing off.” But if we can’t converse with Cicero, Montaigne and Defoe, we can at least read about their conversational expectations. I don’t endorse all of Miller’s conclusions, especially about recent decades, but at least it’s a conversation-starter.

Bedrock: Writers on the Wonders of Geology, Edited by Laurel E. Savoy, Eldridge M Moores, and Judith E. Moores (Trinity University Press.) Our modern sense of time and change began with geology. Rock strata revealed by mining and canal digging, along with fossils discovered in the same digs, led to an expanded sense of the earth’s age, and inspired Darwin in his consideration of biological evolution. This anthology takes a very wide view of the subject, including excerpts from writers like Mark Twain, James Joyce, Lucille Clifton and Michael Ondaatje as well as Darwin, Loren Eiseley, John McPhee and Paul Shepard in sections titled “Of Rock and Stone,” “Deep Time,” “Faults, Earthquakes and Tsunamis,” “Volcanoes and Eruptions” (where Ursula Le Guin appears along with Pliny the Younger), “On Mountains and Highlands,” Rivers to the Sea,” “The Work of Ice,” “Wind and Desert” and “Living on Earth.” These pieces add up to senses of where geologic matters fit into the web of life, including how humans interact with these objects and forces—neither animal or vegetable but in some sense, so many clearly feel, alive—in many times and cultures.

Sunday, May 21, 2006

Breaking Point

Made to Break

Technology and Obsolescence in America

By Giles Slade

Harvard University Press

by William S. Kowinski

As Steven Wright famously said, "You can't have everything. Where would you put it?" So you get rid of the old stuff, but what makes it old? The idea of products built not to last irks us, but for a variety of reasons we routinely discard devices that work just fine. Obsolescence by any other name has helped nourish a sweet economy, but a hidden cost is coming due fast, in the poisonous waste quickly overwhelming the world's capacity to deal with it.

Review continues in today's San Francisco Chronicle Book Review.

Made to Break

Technology and Obsolescence in America

By Giles Slade

Harvard University Press

by William S. Kowinski

As Steven Wright famously said, "You can't have everything. Where would you put it?" So you get rid of the old stuff, but what makes it old? The idea of products built not to last irks us, but for a variety of reasons we routinely discard devices that work just fine. Obsolescence by any other name has helped nourish a sweet economy, but a hidden cost is coming due fast, in the poisonous waste quickly overwhelming the world's capacity to deal with it.

Review continues in today's San Francisco Chronicle Book Review.

Monday, May 15, 2006

Saving Humanity: a Dirty Job for Post-Humans in the Post-Apocalypse

everfree

By Nick Sagan

Penguin Books

by William S. Kowinski

In the future of Nick Sagan’s science fiction trilogy which concludes with this volume, humanity has been wiped out by a plague called Black Ep, except for some bioengineered children kept in the dark of a Virtual Reality world, and caches of “frozen” survivors awaiting the day their “posthuman” experimental children find a cure and thaw them out.

In idlewild, we met the children as adolescents, as they discovered that their virtual reality fantasy world and their “real world” were the same. They rejoin the empty husk of a devastated planet, have progeny of their own (in various ways),face a second plague and eventually find the cure in volume 2, edenborn. There are losses, crimes, passions, discoveries, deaths and illuminations along the way.

In volume three, everfree, Rebirth and Response is followed by Recovery, as the remaining posthumans, now in early adulthood, revive and cure the survivors, and try to supervise a shaky new world.

Fans of idlewild will be happy to find that the boy who calls himself Halloween, that book’s main character and voice who was largely absent from the middle volume, is back in charge in volume 3. But in one of this trilogy’s many achievements, not so usual in science fiction, he is demonstrably matured. The fire of the cyber-punk is still there, however, and that fuels a forward momentum in this tale’s telling, more like idlewild than the more measured polyphony of edenborn.

For a trilogy set in the same consistent universe it creates, these three books are remarkably different in style and narrative approach; the style and the events of each are part of their separate visions as they fit into the larger development of this story. Everfree has what a concluding volume must (concluding, but not necessarily the last in this universe---the ending has some openings for more): a fast-unfolding story, lots happening and developing, plot and character questions answered, and fates resolved, at least for now.

Without giving too much away, Sagan’s vision of this future is annoyingly realistic: the humanity that gets unfrozen consists of the people rich enough to afford the process, and so they are the neurotic connivers and self-important spoilers of a decadent autocracy. Something like waking up the dregs of Halliburton and the Bush billionaires, combined with the spaceship of castoff p.r. flacks, interior designers and middle managers that originally populated the earth in Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy mythology. Plus the soldiers they had frozen with them—a nice pharaohic touch. It makes sense, unfortunately.

Halloween---now a non-computerized Hal—is chief of security, the Worf in this world of revived wolves. The posthumans try to institute a better society, but it takes some tricks to pull it off, barely. That’s all I’ll say.

There are surprises and twists to keep the pages turning, especially in the book’s first and third sections, with a reprise of the multi-voice character study of the middle volume in between, recapitulating the trilogy’s form. Hal’s voice is strong and his take on things is fascinating, but the book speeds forward on punchy, pithy dialogue, detective novel-style. At the same time, there's impressive erudition and philosophical teasings that keep things moving on other levels. In one sense, everfree explores humans as political animals.

As for the driving ideas, I’m not sure I buy Nick Sagan’s interpretation of evolutionary genetics (too much chimp and not enough Bonobo, if you catch my drift. If not, check out Frans de Waal’s Our Inner Ape, which not only shows that nonviolent conflict resolution and even compassion are genetically dominant in Bonobos, but that more aggressive chimps can learn these techniques.) But the actual action is totally believable.

Exploring the nature of freedom seems part of the action as well, and in the end there is a sense of freedom as just another word for nothing left to win, which I'm also not sure I buy, but it sure is interesting.

But this isn't a philosophical postcard from the post-apocalypse: it's a novel. Beyond the satisfying plotting and storytelling (including a slapstick scene involving the original Bill of Rights) the character development, particularly of Hal, is most impressive. Sagan’s handling of character has grown enormously since idlewild, which had great young characters but was a little shaky otherwise. Edenborn was valiantly successful in creating non-western characters with non-whitebread American sensibilities (as well as a classically creepy yet thoroughly contemporary female villain.) Everfree sketches a panoply of new adult characters with a sure hand, as well as convincingly following the maturing lives of figures familiar from the previous two books.

I suppose edenborn is still my favorite (for the writing and several characters that exist only in its pages) but this is a close second. It’s the most provocative, especially when one ponders what trying to build a better society after the apocalypse might really be like.

This book has all the pleasures of a good adventure story and a science fiction novel, even apart from the previous books. But in context of the triology, there are multiple rewards in character as well as action and ideas that pay off in this volume. Everfree is an exciting ride through an imaginative and believable world, with ideas to ponder, characters to wonder about, and good writing to savor. And the ending is definitely worth the ride, though don’t be surprised if you still want more.

Sunday, April 30, 2006

The Trends in Fads: What We Meme When We Say "New and Improved"

Flavor of the Month: Why Smart People Fall for Fads

by Joel Best

University of California Press

Note: A slightly different version of this review appears today in the San Francisco Chronicle.

by William S. Kowinski

A fad, says the Oxford English Dictionary, is "a peculiar notion as to the right way of doing something." Its traditional reference has been to "a pet project, especially of social and political reform, to which an exaggerated importance is attributed."

Fads define themselves by being the absolute right answer, quickly replaced by the next one. The only way to lose weight is: cut calories, low carb, low fat (and carbon loading), high fiber, milkshakes, low carb again. Joel Best's book focuses on institutional fads, that suddenly dominate management meetings, training sessions, newsletters and retreats, before they wanly disappear and are replaced by the next bright promise. For instance, in business over the past decade or so, there's been: quality management, Excellence, Theory Z, paradigm shifts, fire-walking, business process re-engineering, the Fifth Discipline and Six Sigma, among others. Academics will be wearily familiar with: distance learning, service learning, online learning, zero-based budgeting, the demographic bulge, the demographic bust.

Best analyzes the lifecycle of institutional fads, how (in his terminology) they emerge, surge, diffuse and are purged. Fads are made possible by networks of fast-moving information and an either/or mentality that demands a single answer to perceived problems. Best writes that educators, alarmed that some children are slow to learn to read, have instituted a series of new regimens concentrating on one key method, such as phonics, which emphasizes sounding out words in parts, or "whole language" (also called "word recognition") that emphasizes words in context. Best points out that both methods are essential, and that favoring one over the other has not altered the fundamental fact that some children learn to read faster than others.

Not all fads represent pendulum swings, and beyond the talking points, Best engages in some deeper analysis of fad-making mechanisms. But casual readers will probably be most amused by the many anonymous commentaries Best reproduces, that appear on office bulletin boards and these days circulate by email, such as the American solution to losing a rowing match with Japan in which it had one person rowing and eight steering: after a consultant study and management reorganization, the American team added three steering directors and two steering supervisors. When that didn't work, they laid off the rower. This office folklore is frequently wittier and wiser than any signed analysis, with the possible exception of the Dilbert cartoon strip (which uses ideas suggested by readers.)

Why do we fall for fads? Why do fools fall in love? Novelty attracts our nervous systems, our faith is progress and our passion is hope. Something new might be the next great thing (the last one sure wasn't), no matter how bizarre it seems at first. They all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round. They all laughed when Edison recorded sound.

Some fads begin with a really neat word. Best mentions chaos theory, which began in physics but quickly spread to areas like analyzing literature, where it was deployed with little understanding of its original meaning. A more recent example might be meme, which biologist Richard Dawkins proposed as the mental analogue of the gene. As dubious as Dawkins original claim might be, the word itself has spread like wildfire, but used essentially to mean an idea quickly replicated through the media. It is the latest fad for a word that means: the latest fad.

Although Best barely mentions it, elements of many institutional fads survive the surge and purge cycle to settle into the synthesis of how things are done. Mission statements, just-in-time supply lines, bench-marking and attention to corporate culture were all parts of 1980s management fads like Excellence and Quality. Now they're so normal that young managers might be surprised to learn they are newer than video stores.

That's because these flavors aren't ice cream-they're basically ideas, however initially inflated the claims. They enter the mix for experiment, evaluation and transformation, becoming part of how business, education and our lives are managed and mis-managed. It's also been known for years that one reason many good ideas become failed fads is that management tries to impose practices on the employees who must implement them without taking their practical modifications or point of view seriously. Instead, these dogmatic approaches become the hula hoops employees must jump through.

There's a lot more to be said about the subject, like why managers are so susceptible to magical thinking (I call it the Blue Angel Syndrome---what do you think, have I got a book there?) But this book is a clearly written and overdue overview and analysis of the subject. Besides, there may be just enough to make this book on fads into one: it offers a simple step-by-step explanation with catchy names (I see a Power Point accompaniment) that will entertain business and academic conventions for the usual year.

There is a problem, however. Flavor of the Month is a well-worn name for the phenomenon. A fad needs a brand-new catchy title, like The Tipping Point, Flow, The Peter Principle, Future Shock, Psychobabble (the title of a forgotten book by Richard Rosen) or even The Malling of America.

Flavor of the Month: Why Smart People Fall for Fads

by Joel Best

University of California Press

Note: A slightly different version of this review appears today in the San Francisco Chronicle.

by William S. Kowinski

A fad, says the Oxford English Dictionary, is "a peculiar notion as to the right way of doing something." Its traditional reference has been to "a pet project, especially of social and political reform, to which an exaggerated importance is attributed."

Fads define themselves by being the absolute right answer, quickly replaced by the next one. The only way to lose weight is: cut calories, low carb, low fat (and carbon loading), high fiber, milkshakes, low carb again. Joel Best's book focuses on institutional fads, that suddenly dominate management meetings, training sessions, newsletters and retreats, before they wanly disappear and are replaced by the next bright promise. For instance, in business over the past decade or so, there's been: quality management, Excellence, Theory Z, paradigm shifts, fire-walking, business process re-engineering, the Fifth Discipline and Six Sigma, among others. Academics will be wearily familiar with: distance learning, service learning, online learning, zero-based budgeting, the demographic bulge, the demographic bust.

Best analyzes the lifecycle of institutional fads, how (in his terminology) they emerge, surge, diffuse and are purged. Fads are made possible by networks of fast-moving information and an either/or mentality that demands a single answer to perceived problems. Best writes that educators, alarmed that some children are slow to learn to read, have instituted a series of new regimens concentrating on one key method, such as phonics, which emphasizes sounding out words in parts, or "whole language" (also called "word recognition") that emphasizes words in context. Best points out that both methods are essential, and that favoring one over the other has not altered the fundamental fact that some children learn to read faster than others.

Not all fads represent pendulum swings, and beyond the talking points, Best engages in some deeper analysis of fad-making mechanisms. But casual readers will probably be most amused by the many anonymous commentaries Best reproduces, that appear on office bulletin boards and these days circulate by email, such as the American solution to losing a rowing match with Japan in which it had one person rowing and eight steering: after a consultant study and management reorganization, the American team added three steering directors and two steering supervisors. When that didn't work, they laid off the rower. This office folklore is frequently wittier and wiser than any signed analysis, with the possible exception of the Dilbert cartoon strip (which uses ideas suggested by readers.)

Why do we fall for fads? Why do fools fall in love? Novelty attracts our nervous systems, our faith is progress and our passion is hope. Something new might be the next great thing (the last one sure wasn't), no matter how bizarre it seems at first. They all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round. They all laughed when Edison recorded sound.

Some fads begin with a really neat word. Best mentions chaos theory, which began in physics but quickly spread to areas like analyzing literature, where it was deployed with little understanding of its original meaning. A more recent example might be meme, which biologist Richard Dawkins proposed as the mental analogue of the gene. As dubious as Dawkins original claim might be, the word itself has spread like wildfire, but used essentially to mean an idea quickly replicated through the media. It is the latest fad for a word that means: the latest fad.

Although Best barely mentions it, elements of many institutional fads survive the surge and purge cycle to settle into the synthesis of how things are done. Mission statements, just-in-time supply lines, bench-marking and attention to corporate culture were all parts of 1980s management fads like Excellence and Quality. Now they're so normal that young managers might be surprised to learn they are newer than video stores.

That's because these flavors aren't ice cream-they're basically ideas, however initially inflated the claims. They enter the mix for experiment, evaluation and transformation, becoming part of how business, education and our lives are managed and mis-managed. It's also been known for years that one reason many good ideas become failed fads is that management tries to impose practices on the employees who must implement them without taking their practical modifications or point of view seriously. Instead, these dogmatic approaches become the hula hoops employees must jump through.

There's a lot more to be said about the subject, like why managers are so susceptible to magical thinking (I call it the Blue Angel Syndrome---what do you think, have I got a book there?) But this book is a clearly written and overdue overview and analysis of the subject. Besides, there may be just enough to make this book on fads into one: it offers a simple step-by-step explanation with catchy names (I see a Power Point accompaniment) that will entertain business and academic conventions for the usual year.

There is a problem, however. Flavor of the Month is a well-worn name for the phenomenon. A fad needs a brand-new catchy title, like The Tipping Point, Flow, The Peter Principle, Future Shock, Psychobabble (the title of a forgotten book by Richard Rosen) or even The Malling of America.

Saturday, April 29, 2006

To Be the Hero of Your Own Life

The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live By

by Dan P. McAdams

Oxford University Press

by William S. Kowinski

When Oprah Winfrey called the Larry King Show--the Queen of Talk calling the King, so to speak (although she's Queen of a larger land)--she defended author James Frey, an act she has since repudiated. (If you're not sure who I'm talking about, there are several posts below this one, from earlier this year, that should refresh your memory.) She noted that while some of what he'd written wasn't altogether true, the power of his story remained intact: a story of redemption. She used that word: redemption. Redemption as the payoff that motivates hope was so powerful to her that she was temporarily willing to overlook what was soon revealed to be large scale deception. When she turned against Frey, it was with a passion due presumably to the damage he'd done, not only to credibility, but to hope, and his manipulation of redemption.

Though Frey isn't mentioned in psychologist Dan P. McAdams' book, Oprah is a major character and example of McAdams' thesis that redemption is a primal theme in the life narratives of "generative" people--people who accomplish a lot (he probably could have vastly increased sales of this book simply by calling them "successful.")

"If you are looking for the redemptive self, you should know that it is not hard to find," he writes. "You need go no further than the Oprah Winfrey show, the self-help aisle at your local bookstore, or Hollywood's latest drama about the humble hero who overcame all the odds to find vivid expressions of the power of redemption in human lives."

But it's not just Oprah's show, but her own story--her life as she describes it-- that exemplifies the redemption theme. McAdams shows how it is deep in the American way of looking at things, and he illustrates how it typically plays out according to race and class and historical context. But essential to this basically melodramatic theme is the idea that bad things happen for a reason; they happen to form and motivate redemption.

McAdams finds the theme in Emerson and in American slave narratives; in the Gettysburg Address and in the stories that generative people tell about themselves. Redemption requires suffering, and it makes violence and deprivation to the innocent, or visited seemingly at random, a comprehensible part of a story with a happy ending. It channels guilt and regret for past mistakes into a narrative of personal triumph, overcoming those errors, sins and crimes. It provides hope (and perhaps also additional guilt) to those born into devastating circumstances or subjugated groups that an individual can overcome the obstacles and rise above their apparent fate.

This is a well-written book that makes scholarship and theory accessible. It's not the kind of treatment that is itself likely to make it onto the self-help best-seller displays, but McAdams has put his finger on something that he argues is prominently and characteristically American. He explores the inspiring and troubling aspects of the redemption narrative: hope and self-deception, belief in oneself and the belief that one was "chosen" for redemption and success.

There's plenty of content here, and generous notes to add further depth and texture. Maybe we all wonder, with David Copperfield, if we're going to be the hero of our own story. It seems we Americans go to some length to make sure we are.

The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live By

by Dan P. McAdams

Oxford University Press

by William S. Kowinski

When Oprah Winfrey called the Larry King Show--the Queen of Talk calling the King, so to speak (although she's Queen of a larger land)--she defended author James Frey, an act she has since repudiated. (If you're not sure who I'm talking about, there are several posts below this one, from earlier this year, that should refresh your memory.) She noted that while some of what he'd written wasn't altogether true, the power of his story remained intact: a story of redemption. She used that word: redemption. Redemption as the payoff that motivates hope was so powerful to her that she was temporarily willing to overlook what was soon revealed to be large scale deception. When she turned against Frey, it was with a passion due presumably to the damage he'd done, not only to credibility, but to hope, and his manipulation of redemption.

Though Frey isn't mentioned in psychologist Dan P. McAdams' book, Oprah is a major character and example of McAdams' thesis that redemption is a primal theme in the life narratives of "generative" people--people who accomplish a lot (he probably could have vastly increased sales of this book simply by calling them "successful.")

"If you are looking for the redemptive self, you should know that it is not hard to find," he writes. "You need go no further than the Oprah Winfrey show, the self-help aisle at your local bookstore, or Hollywood's latest drama about the humble hero who overcame all the odds to find vivid expressions of the power of redemption in human lives."

But it's not just Oprah's show, but her own story--her life as she describes it-- that exemplifies the redemption theme. McAdams shows how it is deep in the American way of looking at things, and he illustrates how it typically plays out according to race and class and historical context. But essential to this basically melodramatic theme is the idea that bad things happen for a reason; they happen to form and motivate redemption.

McAdams finds the theme in Emerson and in American slave narratives; in the Gettysburg Address and in the stories that generative people tell about themselves. Redemption requires suffering, and it makes violence and deprivation to the innocent, or visited seemingly at random, a comprehensible part of a story with a happy ending. It channels guilt and regret for past mistakes into a narrative of personal triumph, overcoming those errors, sins and crimes. It provides hope (and perhaps also additional guilt) to those born into devastating circumstances or subjugated groups that an individual can overcome the obstacles and rise above their apparent fate.

This is a well-written book that makes scholarship and theory accessible. It's not the kind of treatment that is itself likely to make it onto the self-help best-seller displays, but McAdams has put his finger on something that he argues is prominently and characteristically American. He explores the inspiring and troubling aspects of the redemption narrative: hope and self-deception, belief in oneself and the belief that one was "chosen" for redemption and success.

There's plenty of content here, and generous notes to add further depth and texture. Maybe we all wonder, with David Copperfield, if we're going to be the hero of our own story. It seems we Americans go to some length to make sure we are.

Thursday, February 02, 2006

Wednesday, February 01, 2006

I've written several times at Dreaming Up Daily on the James Frey fray over the past week or so. I'm presenting those pieces here, one after the other, beginning in book-style with the first at the top and the rest following.

A Million Easy Pieces

(originally posted January 24, 2006)

Sunday's San Francisco Chronicle Insight published two opinions concerning James Frey and his fabrications in his bestselling memoir, A Million Little Pieces: one by Martha Sherrill, a young writer whose first novel has just been published, and the other by novelist Cynthia Bass.

Sherrill had herself accepted a big publisher advance to write a memoir but found it paralyzing. She felt more comfortable turning the same material into a novel, though she found that readers were still hungry to know what in it was "real" or "true." Though the controversy over the accuracy of Frey's memoir has provided him with even more publicity, she writes that "I do think there's a way he might be helping novelists everywhere. Once they're over their shock and sense of betrayal, Frey's readers might come to realize the fictional bits were some of the best moments in his book -- that without those thrilling embellishments it would have been just another true story. Maybe next time they go to the bookstore, they'll decide to try the real thing: an honest-to-god novel. "

Novelist Cynthia Bass writes that the Frey fray should be a cautionary tale, about just how much "truth" is in any non-fiction. The vagaries of memory, the limitation of one perspective, and the exegencies of telling a good story mitigate against certainty. She points out that before recently memoirs were by famous people concerning public events, with facts that could be easily checked. But memoirs these days are personal stories by previously non-famous people, usually of lurid events--addictions, incest, etc.-- with an arc of redemption. Their factuality has to be taken on faith. "If I claim to have hit a home run at my last at-bat at Fenway, you can look it up. If I claim to have hit a home run at my last at-bat at Patrick Henry Elementary, that's impossible to confirm. "Yet the authenticity of personal memoirs is even more important to readers (hence the Frey fray.)"The unspoken bond of trust between reader and author is breached. Deliberately doing this to a reader is, for an author and a publisher, as close to a sin as you can get in the world of writing. "

Bass acknowledges that new writers are under tremendous pressure to write in the memoir form because it is potentially so much more commercial than all but a few novels (Only the latest Harry Potter novel has apparently been outselling Frey's first book.) She admits that she was asked to write a memoir instead of a novel and was tempted; and that other writers she saw commenting on the Frey fray found nothing wrong in whatever inventing he did. "The prevailing sentiment is to do whatever it takes. Which is just what Frey did. After failing to sell his book as fiction, he said it was a memoir."

She suggests "a rearrangement of attitude: less cynicism from the producers, and more from the consumers. There's nothing more dispiriting than learning what you thought was true -- what you hoped was true -- was a lie, perpetrated for money, ambition and fame. "But while both Sherrill and Bass make valid points, neither they nor Frey have addressed the most importance qualities of non-fiction or fiction.

I haven't read Frey's book but just the excerpts I saw in the now-famous Smoking Gun analysis were so plainly outrageous, melodramatic and exaggerated, that I didn't believe them on their face. I hope for the sake of his readers than in context they were made more convincing by better writing.

Clearly, the memoir's popularity has something to do with an immense hunger for certain kinds of redemption stories. That is apparently more important than any fact to these readers---the journey from sin to redemption---and especially the redemption-- forms "the truth" of the story for them. Perhaps these memoirs and their redemption stories are an outgrowth of the recovery movement, and the spreading of various new ways of approaching behavior and the big questions of life, from simplified psychology to the varieties of religious experience.

But some prominent writers and teachers, like philosopher Martha Nussbaum (Poetic Justice)and psychologist Robert Coles (The Call of Stories) have found that real literature still speaks to people on a very personal level, and helps them see themselves and the world around them in new ways.What troubles me beyond truth in labeling is the simplistic analysis of fiction as embroidered memoir. Novels are more than stuff that happened, touched up for effect, like a Photoshop portrait. There is little sense in what either of these novelists said of what a literary work can be, of its complexities and resonances. Children don't seem to have any problem dealing with the literary intentions of the Harry Potter books, so it's not like contemporary readers can't handle it.

Novels are more than "thrilling embellishments." They are stories with their own integrity, following their own necessities. Literature is something alive ; truth is in the reader.The cynicism of the writers Bass refers to is pretty troubling, especially in an age of institutionalized cynicism, as represented by current commercial capitalism and political fundamentalism. While I see nonfiction as a literary form, I believe that what Frey did was beyond the bounds of nonfiction storytelling; it was dishonest. What little I read wasn't even good pulp fiction, so the intention to deceive for profit wouldn't surprise me in a work that obviously stresses the extreme for easy effect. If so, it's mirror cynicism: a paint-by-number Best-Selling Memoir using the most lurid colors in the box.

We face complex problems in the present affecting the future, and we will face ever more complex situations requiring relatively quick decisions in that future. We need leaders and citizens who can apply the complexities learned from literature to understanding the dimensions of the future and to help them craft solutions to the problems that emerge. This is not a pipedream: it has been a feature of leaders in the West and East throughout history, though not uniformly, and its absense in current U.S. leadership is tragically clear.

It is also not a panacea, as history shows, especially if not widely shared by the citizenry. But literature is accessible to more citizens than ever before, as are opportunities to acquire the skills to augment intuitive responses. These skills are as just as important for an informed citizenry. Lacking leadership in this regard, it becomes a personal and family responsibility.

A Million Easy Pieces

(originally posted January 24, 2006)

Sunday's San Francisco Chronicle Insight published two opinions concerning James Frey and his fabrications in his bestselling memoir, A Million Little Pieces: one by Martha Sherrill, a young writer whose first novel has just been published, and the other by novelist Cynthia Bass.